Architects of Russia in the second half of the 18th century

The second half of the 18th century in Russian history is the stabilization of the Russian political system after a protracted era of palace coups, the long-term reign of Elizabeth Petrovna and Catherine II. Classicism became the main artistic style.

Vasily Ivanovich Bazhenov(1738-1799) - a man who fully reflected the ideals, successes and failures of his era. A native of Kaluga province. The son of a village psalm-reader. He was sent to study at the Slavic-Greek-Latin Academy. He attracted attention with his successes in science. He was recommended to the Ukhtomsky school, from which all the major architects of that era came. He was friends with Fonvizin and Novikov. Studied in Paris and Rome. In St. Petersburg, Bazhenov was not fully in demand, so he moved to Moscow. There he is engaged in the repair and reconstruction of the Kremlin ensemble. This was exactly the job Bazhenov was waiting for. However, the project was not destined to be fully realized, which was a terrible blow for the architect.

Pashkov House in Moscow (1784-1786) - a structure considered the creation of Bazhenov. However, no serious documents confirming Bazhenov’s authorship have survived. Only oral rumor attributes this building to Bazhenov. This is one of the buildings of the current State Library. The house was built by order of the son of Peter the Great’s orderly. He was a quirky man, rich enough to afford an unusual project in the center of Moscow directly opposite the Kremlin. For a long time, the Pashkov House was the only place from where one could look at the Kremlin towers from above. The central volume with a columned portico and a round rotunda turret at the top, and the side wings, which, being a single part of this house, still resemble open wings, as if dissolving into the surrounding air and landscape; as if they allow this building, spread out, to breathe, live, and fly over Moscow. Brigadier Pashkov turned a small garden in front of his house into a greenhouse, into a zoo, where parrots, peacocks, and wild animals roamed in cages and at large. And people clung to the fence bars, admiring this fantastic spectacle. And the garden, and strange creatures, and the house in which the unsociable owner of all this beauty lived alone. The compositional basis of the building is the scheme inherent in the then estates of the landowners. Thanks to one-story galleries, the central three-story building is connected to two-story side buildings. A two-flight staircase descends from the central building down the hill. All parts of the composition are independent and complete. Pilasters serve as decoration for the walls of the house. Four-column porticoes accent the center of the main and courtyard facades. There are statues on the sides. The crown of the building is a round belvedere, which is surrounded by an Ionic colonnade. The edge of the roof is decorated with a balustrade with vases. The side buildings, where the columns of the porticoes with pediments are located, are made in the tradition of the Ionic order. Thus began the emergence of a new artistic style for Russian art - classicism.

Engineering (Mikhailovsky) castle in St. Petersburg(1780-1797). Until 1823, the castle was called Mikhailovsky and got its name from the Church of the Archangel Michael built into it. This whimsical structure has a square plan with rounded corners, into which an octagonal courtyard is inscribed. It seemed strange to contemporaries, accustomed to classicist buildings. The townspeople were surprised by the unusual treatment of the facades and the red and white color of the building, which was never used in classicism. The palace was built as an impregnable castle, surrounded by moats and drawbridges. The author of the original project was Emperor Paul I himself, who very closely followed the construction of the palace, where, by a fatal coincidence, he was killed by the conspirators.

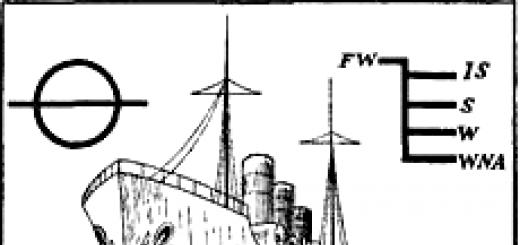

Matvey Fedorovich Kazakov (1738-1812) Senate building in the Moscow Kremlin(1776-1787). The general plan of the building received a compact and at the same time geometrically simple triangle shape. It includes a courtyard, which is divided into three parts by several transverse buildings. The main facade is designed in the form of a four-column portico with a pediment. Here is the entrance to the central part of the courtyard. The round domed hall is the semantic center of the entire composition of the Senate. The colonnade, made in the tradition of the Ionic order, is located on a high rusticated plinth. It is crowned with a powerful, cracked cornice. Above it, right on the drum, is the dome of the round hall. The architect managed to organically include the Senate building into the Kremlin architectural ensemble. The originality of the composition lies in the fact that the dome of the round hall itself is on the same axis with the Senate Tower of the Kremlin Wall. The latter denotes the transverse axis of Red Square. Thus, a single harmonious image of the Kremlin emerges.

Bartolomeo Rastrelli(1700-1771), who in Russia was called in his own manner Bartholomew Varfolomeevich, the most striking figure of the mid-18th century, working in the Russian Baroque style.

Great Catherine Palace in Tsarskoe Selo(1752-1757). This building is complex in its composition, created on the site of an old palace. The building is under one roof. All buildings of the former palace have been leveled. This transforms the former galleries into a great hall and tall state apartments. Outside, the right corner of the building above the main entrance is crowned with a dome with one chapter. The five-domed church corresponds to this dome at the other end of the palace. The composition of the palace's interiors is built on the effect of an endless length of a suite of halls, living rooms and other ceremonial rooms. The grandiose palace is distinguished by its exceptional splendor of plastic and decorative work. Its facades are full of rich stucco decorations. And the paint of the building is based on a combination of intense blue walls, white - architectural details, gilding - sculptures and domes.

Winter Palace in St. Petersburg(1754-1762). This building is the apotheosis of the Baroque style. The plan is a simple square with a courtyard. Its facades face the Neva, the Admiralty and Palace Square. The facades of the palace form like folds of an endless ribbon. The architect solves each facade in his own way, varying the lush decoration and the changing rhythm of the column. The stepped cornice follows all the breaks in the walls. The size of the building is enormous - it has more than a thousand rooms, arranged in enfilades, decorated with carvings, moldings and gilding. The main staircase is one of the most luxurious interiors of the Winter Palace. It occupies a huge space the entire height of the building. The lampshade depicting the gods of Olympus creates a bright colorful accent. The interiors designed by Rastrelli always had a purely secular character. This is the decision of the large church of the Winter Palace. Its interior is like a large palace ceremonial hall, divided into three parts. The central part ended with a magnificent carved iconostasis.

Peterhof. The main importance here is the fountains and the water itself. They are driven by the natural pressure of water supplied from the Ropshin heights. According to the artist Alexandre Benois, Peter was building the residence of the king of the seas. Fountains are a symbolic expression of the watery kingdom, clouds and splashes of the sea that splashes off the shores of Peterhof. The system of fountains and water cascades is decorated with numerous sculptures. The Samson fountain was made by the outstanding sculptor Kozlovsky.

J. B. Vallin-Delamot and A. F. Kokorinov. Academy of Arts(1764-1788). It occupies a total of an entire block on the Neva embankment. The building follows a strict plan, which is represented by a circle inscribed in it. The circle is intended to serve as a yard for walking. The building is equally high and consists of four floors. They are divided in pairs and form the load-bearing part of the building, as well as its lightweight top. It is impossible not to feel the spirit of the times in the fundamentally new solution of the ornament - strict and geometric. The attitude towards the traditional order system is also becoming more canonical.

Ivan Egorovich Starov (1745-1808) - another architect who worked within the framework of classicism. He owns the Tauride Palace, built for the favorite of Empress Catherine II - His Serene Highness Prince Potemkin-Tavrichesky. The construction itself marked the fact of his victory over the Ottoman Turks. The palace took six years to build and was completed in 1789. The lobby was decorated with yakhont and granite pillars. In the domed hall there were faience Dutch ovens, decorated with azure and gold. In the center there was a huge Catherine's hall - the Winter Garden. The Empress herself loved to be here. International receptions were held and luxurious balls were held. At the palace there was a greenhouse in which watermelons, melons, and peaches were grown all year round. Emperor Paul gave the palace to the Horse Guards. The parquet was dismantled and taken to the Mikhailovsky Castle, which was under construction. It was here that the State Duma was first established in 1906.

I.M.Schmidt

The eighteenth century is a time of remarkable flowering of Russian architecture. Continuing; on the one hand, their national traditions, Russian masters during this period began to actively master the experience of contemporary Western European architecture, reworking its principles in relation to the specific historical needs and conditions of their country. They have greatly enriched world architecture, introducing unique features into its development.

For Russian architecture of the 18th century. Characterized by the decisive predominance of secular architecture over religious architecture, the breadth of urban plans and solutions. A new capital was being built - St. Petersburg, and as the state strengthened, old cities were expanded and rebuilt.

The decrees of Peter I contained specific orders relating to architecture and construction. Thus, his special order prescribed that the facades of newly constructed buildings should be placed on the red line of the streets, while in ancient Russian cities houses were often located in the depths of courtyards, behind various outbuildings.

According to a number of its stylistic features, Russian architecture of the first half of the 18th century. can undoubtedly be compared with the Baroque style dominant in Europe.

Nevertheless, a direct analogy cannot be drawn here. Russian architecture - especially from the time of Peter the Great - had a much greater simplicity of form than was characteristic of the late Baroque style in the West. In its ideological content, it affirmed the patriotic ideas of the greatness of the Russian state.

One of the most remarkable buildings of the early 18th century is the Arsenal building in the Moscow Kremlin (1702-1736; architects Dmitry Ivanov, Mikhail Choglokov and Christoph Conrad). The large length of the building, the calm surface of the walls with sparsely spaced windows and the solemn and monumental design of the main gate clearly indicate a new direction in architecture. A completely unique solution is the small paired Arsenal windows, which have a semi-circular finish and huge external slopes like deep niches.

New trends also penetrated into religious architecture. A striking example of this is the Church of the Archangel Gabriel, better known as the Menshikov Tower. It was built in 1704-1707. in Moscow, on the territory of the estate of A. D. Menshikov near Chistye Prudy, by the architect Ivan Petrovich Zarudny (died in 1727). Before the fire of 1723 (caused by a lightning strike), the Menshikov Tower - like the bell tower of the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg, which was built shortly after - was crowned with a high wooden spire, at the end of which was a gilded copper figure of the archangel. The height of this church exceeded the bell tower of Ivan the Great in the Kremlin ( The light, elongated dome of this church, which now has a unique shape, was made already at the beginning of the 19th century. The restoration of the church dates back to 1780.).

I.P. 3arudny. Church of the Archangel Gabriel (“Menshikov Tower”) in Moscow. 1704-1707 View from the southwest.

The Menshikov Tower is characteristic of Russian church architecture of the late 17th century. a composition of several tiers - “octagons” on a “quadruple”. At the same time, compared to the 17th century. here new trends are clearly outlined and new architectural techniques are used. Particularly bold and innovative was the use of a high spire in a church building, which was then so successfully used by St. Petersburg architects. Zarudny's appeal to the classical methods of the order system is characteristic. In particular, columns with Corinthian capitals, unusual for ancient Russian architecture, were introduced with great artistic tact. And quite boldly - powerful volutes flanking the main entrance to the temple and giving it a special monumentality, originality and solemnity.

Zarudny also created wooden triumphal gates in Moscow - in honor of the Poltava victory (1709) and the conclusion of the Nystadt Peace (1721). Since the time of Peter the Great, the erection of triumphal arches has become a frequent phenomenon in the history of Russian architecture. Both wooden and permanent (stone) triumphal gates were usually richly decorated with sculpture. These buildings were monuments to the military glory of the Russian people and largely contributed to the decorative design of the city.

Plan of the central part of St. Petersburg in the 18th century.

With the greatest clarity and completeness, the new qualities of Russian architecture of the 18th century. manifested themselves in the architecture of St. Petersburg. The new Russian capital was founded in 1703 and was built unusually quickly.

From an architectural point of view, St. Petersburg is of particular interest. It is the only capital city in Europe that emerged entirely in the 18th century. Its appearance vividly reflected not only the unique directions, styles and individual talents of the architects of the 18th century, but also the progressive principles of urban planning of that time, in particular planning. In addition to the brilliantly designed “three-beam” layout of the center of St. Petersburg, high urban planning art was manifested in the creation of complete ensembles and in the magnificent development of the embankments. From the very beginning, the indissoluble architectural and artistic unity of the city and its waterways represented one of the most important advantages and unique beauty of St. Petersburg. The formation of the architectural appearance of St. Petersburg in the first half of the 18th century. associated mainly with the activities of architects D. Trezzini, M. Zemtsov, I. Korobov and P. Eropkin.

Domenico Trezzini (c. 1670-1734) was one of those foreign architects who, having arrived in Russia at the invitation of Peter I, remained here for many years, or even until the end of their lives. The name Trezzini is associated with many buildings of early St. Petersburg; he owns “exemplary”, that is, standard designs of residential buildings, palaces, temples, and various civil structures.

Domenico Trezzini. Peter and Paul Cathedral in Leningrad. 1712-1733 View from the northwest.

Trezzini did not work alone. A group of Russian architects worked with him, whose role in the creation of a number of buildings was extremely responsible. Trezzini's best and most significant creation is the famous Peter and Paul Cathedral, built in 1712-1733. The construction is based on the plan of a three-nave basilica. The most remarkable part of the cathedral is its upward-facing bell tower. Just like Zarudny's Menshikov Tower in its original form, the bell tower of the Peter and Paul Cathedral is crowned with a high spire, topped with the figure of an angel. The proud, easy rise of the spire is prepared by all the proportions and architectural forms of the bell tower; a gradual transition from the bell tower itself to the “needle” of the cathedral was thought out. The bell tower of the Peter and Paul Cathedral was conceived and implemented as an architectural dominant in the ensemble of St. Petersburg under construction, as the personification of the greatness of the Russian state, which established its new capital on the shores of the Gulf of Finland.

Trezzini. The building of the Twelve Collegiums in Leningrad. Fragment of the facade.

In 1722-1733 Another well-known Trezzini building is being created - the building of the Twelve Colleges. Strongly elongated in length, the building has twelve sections, each of which is designed as a relatively small but independent house with its own ceiling, pediment and entrance. Trezzini’s favorite strict pilasters in this case are used to unite the two upper floors of the building and emphasize the measured, calm rhythm of the divisions of the facade. The proud, rapid rise of the bell tower of the Peter and Paul Fortress Cathedral and the calm length of the building of the Twelve Colleges - these beautiful architectural contrasts were carried out by Trezzini with the impeccable tact of an outstanding master.

Most of Trezzini's works are characterized by restraint and even rigor in the architectural design of buildings. This is especially noticeable next to the decorative pomp and rich design of buildings of the mid-18th century.

Georg Mattarnovi, Gaetano Chiaveri, M. G. Zemtsov. Kunstkamera in Leningrad. 1718-1734 Facade.

The activities of Mikhail Grigorievich Zemtsov (1686-1743), who initially worked for Trezzini and attracted the attention of Peter I with his talent, were varied. Zemtsov participated, apparently, in all of Trezzini’s major works. He completed the construction of the Kunstkamera building, begun by the architects Georg Johann Mattarnovi and Gaetano Chiaveri, built the churches of Simeon and Anna, Isaac of Dalmatia and a number of other buildings in St. Petersburg.

G. Mattarnovi, G. Chiaveri, M.G.3emtsov. Kunstkamera in Leningrad. Facade.

Peter I attached great importance to the regular development of the city. The famous French architect Jean Baptiste Leblond was invited to Russia to develop a master plan for St. Petersburg. However, the master plan of St. Petersburg drawn up by Leblon had a number of very significant shortcomings. The architect did not take into account the natural development of the city, and his plan suffered largely from abstraction. Leblon's project was only partially implemented in the layout of the streets of Vasilievsky Island. Russian architects made many significant adjustments to its layout of St. Petersburg.

A prominent urban planner of the early 18th century was the architect Pyotr Mikhailovich Eropkin (c. 1698-1740), who gave a remarkable solution to the three-ray layout of the Admiralty part of St. Petersburg (including Nevsky Prospekt). Carrying out a lot of work in the “Commission on St. Petersburg Building” formed in 1737, Eropkin was in charge of the development of other areas of the city. His work ended in the most tragic way. The architect was associated with the Volynsky group, which opposed Biron. Among other prominent members of this group, Eropkin was arrested and executed in 1740.

Eropkin is known not only as a practicing architect, but also as a theorist. He translated the works of Palladio into Russian, and also began work on the scientific treatise “The Position of an Architectural Expedition.” The last work concerning the main issues of Russian architecture was not completed by him; after his execution, this work was completed by Zemtsov and I.K. Korobov (1700-1747), the creator of the first stone building of the Admiralty. Topped with a tall thin spire, echoing the spire of the Peter and Paul Cathedral, the Admiralty Tower, built by Korobov in 1732-1738, became one of the most important architectural landmarks of St. Petersburg.

Definition of the architectural style of the first half of the 18th century. usually causes a lot of controversy among researchers of Russian art. Indeed, the style of the first decades of the 18th century. was complex and often very contradictory. The Western European Baroque style, somewhat modified and more restrained in form, participated in its formation; The influence of Dutch architecture also had an effect. To one degree or another, the influence of the traditions of ancient Russian architecture also made itself felt. A distinctive feature of many of the first buildings of St. Petersburg was the harsh utilitarianism and simplicity of architectural forms. The unique originality of Russian architecture in the first decades of the 18th century. lies, however, not in the complex and sometimes contradictory interweaving of architectural styles, but primarily in the urban planning scope, in the life-affirming power and grandeur of the structures erected during this most important period for the Russian nation.

After the death of Peter I (1725), the extensive civil and industrial construction undertaken on his instructions faded into the background. A new period begins in the development of Russian architecture. The best forces of architects were now directed to palace construction, which assumed an extraordinary scale. From about the 1740s. A distinct Russian Baroque style is established.

In the mid-18th century, the broad career of Bartholomew Varfolomeevich Rastrelli (1700-1771), the son of the famous sculptor K.-B. Rastrelli. The work of Rastrelli the son belongs entirely to Russian art. His work reflected the increased power of the Russian Empire, the wealth of the highest court circles, who were the main customers of the magnificent palaces created by Rastrelli and the team he led.

Johann Braunstein. Hermitage Pavilion in Peterhof (Petrodvorets). 1721-1725

Rastrelli's activities in rebuilding the palace and park ensemble of Peterhof were of great importance. The site for the palace and an extensive garden and park ensemble, which later received the name Peterhof (now Petrodvorets), was planned in 1704 by Peter I himself. In 1714-1717. Monplaisir and the stone Peterhof Palace were built according to the designs of Andreas Schlüter. Subsequently, several architects were involved in the work, including Jean Baptiste Leblond, the main author of the layout of the park and fountains of Peterhof, and I. Braunstein, builder of the Marly and Hermitage pavilions.

From the very beginning, the Peterhof ensemble was conceived as one of the world's largest ensembles of garden structures, sculptures and fountains, rivaling Versailles. The design, magnificent in its integrity, united the Grand Cascade and the grandiose staircase descents framing it with the Large Grotto in the center and towering above the entire palace into one inextricable whole.

Without touching in this case on the complex issue of authorship and the history of construction, which was carried out after Leblon’s sudden death, it should be noted that in 1735 the installation of the sculptural group “Samson tearing the mouth of the lion”, central in its compositional role and ideological concept (the authorship has not been precisely established), which completed the first stage of creating the largest of the regular park ensembles of the 18th century.

In the 1740s. The second stage of construction in Peterhof began, when a grandiose reconstruction of the Great Peterhof Palace was undertaken by the architect Rastrelli. While maintaining some restraint in the design of the old Peterhof Palace, characteristic of the style of Peter the Great's time, Rastrelli nevertheless significantly enhanced its decorative design in the Baroque style. This was especially evident in the design of the left wing with the church and the right wing (the so-called Corps under the coat of arms) that were newly added to the palace. The final of the main stages of the construction of Peterhof dates back to the end of the 18th - the very beginning of the 19th century, when the architect A. N. Voronikhin and a whole galaxy of outstanding masters of Russian sculpture, including Kozlovsky, Martos, Shubin, Shchedrin, Prokofiev, were involved in the work.

In general, Rastrelli’s first projects, dating back to the 1730s, are largely still close to the style of Peter the Great’s time and do not amaze with that luxury

and pomp, which are manifested in his most famous creations - the Great (Catherine) Palace in Tsarskoe Selo (now the city of Pushkin), the Winter Palace and the Smolny Monastery in St. Petersburg.

V.V. Rastrelli. The Great (Catherine) Palace in Tsarskoe Selo (Pushkin). 1752-1756 View from the park.

Having started to create the Catherine Palace (1752-1756), Rastrelli did not rebuild it entirely. In the composition of his grandiose building, he skillfully included the already existing palace buildings of the architects Kvasov and Chevakinsky. Rastrelli combined these relatively small buildings, interconnected by one-story galleries, into one majestic building of a new palace, the facade of which reached three hundred meters in length. Low one-story galleries were built on and thereby raised to the overall height of the horizontal divisions of the palace; the old side buildings were included in the new building as protruding projections.

Both inside and outside, Rastrelli's Catherine Palace was distinguished by its exceptional richness of decorative design, inexhaustible imagination and variety of motifs. The roof of the palace was gilded, and sculptural (also gilded) figures and decorative compositions rose above the balustrade surrounding it. The façade was decorated with mighty figures of Atlanteans and intricate stucco moldings depicting garlands of flowers. The white color of the columns stood out clearly against the blue color of the walls of the building.

The interior space of the Tsarskoye Selo Palace was designed by Rastrelli along the longitudinal axis. The numerous halls of the palace, intended for ceremonial receptions, formed a solemn, beautiful enfilade. The main color combination of interior decoration is gold and white. Abundant gold carvings, images of frolicking cupids, exquisite forms of cartouches and volutes - all this was reflected in the mirrors, and in the evenings, especially on the days of receptions and ceremonies, it was brightly lit by countless candles ( This palace of rare beauty was barbarically looted and set on fire by Nazi troops during the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945. Thanks to the efforts of the masters of Soviet art, the Great Tsarskoye Selo Palace has now been restored, as far as possible.).

In 1754-1762 Rastrelli is building another large structure - the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, which became the basis of the future ensemble of Palace Square.

In contrast to the very elongated Tsarskoye Selo Palace, the Winter Palace is designed in the form of a huge closed rectangle. The main entrance to the palace at that time was located in the spacious internal front courtyard.

V.V. Rastrelli. Winter Palace in Leningrad. 1754-1762 View from Palace Square.

V.V. Rastrelli. Winter Palace in Leningrad. Facade from Palace Square. Fragment.

Considering the location of the Winter Palace, Rastrelli designed the facades of the building differently. Thus, the facade facing south, onto the subsequently formed Palace Square, was designed with a strong plastic accentuation of the central part (where the main entrance to the courtyard is located). On the contrary, the facade of the Winter Palace, facing the Neva, is maintained in a calmer rhythm of volumes and colonnade, thanks to which the length of the building is better perceived.

V.V. Rastrelli. Cathedral of the Smolny Monastery in Leningrad. Fragment of the western facade.

V.V. Rastrelli. Cathedral of the Smolny Monastery in Leningrad. Started in 1748. View from the west.

Rastrelli's activities were mainly aimed at creating palace buildings. But even in church architecture he left an extremely valuable work - the design of the ensemble of the Smolny Monastery in St. Petersburg. The construction of the Smolny Monastery, which began in 1748, lasted for many decades and was completed by the architect V. P. Stasov in the first third of the 19th century. In addition, such an important part of the entire ensemble as the nine-tiered bell tower of the cathedral was never realized. In the composition of the five-domed cathedral and a number of general principles for the design of the ensemble of the monastery, Rastrelli directly proceeded from the traditions of ancient Russian architecture. At the same time, we see here the characteristic features of the architecture of the mid-18th century: the splendor of architectural forms, the inexhaustible richness of decor.

Among Rastrelli’s outstanding creations are the wonderful Stroganov Palace in St. Petersburg (1750-1754), St. Andrew’s Cathedral in Kiev, the Resurrection Cathedral of the New Jerusalem Monastery near Moscow, rebuilt according to his design, the wooden two-story Annenhof Palace in Moscow, which has not survived to this day, and others.

If Rastrelli's activities took place mainly in St. Petersburg, then another outstanding Russian architect, Korobov's student Dmitry Vasilyevich Ukhtomsky (1719-1775), lived and worked in Moscow. Two remarkable monuments of Russian architecture of the mid-18th century are associated with his name: the bell tower of the Trinity-Sergius Lavra (1740-1770) and the stone Red Gate in Moscow (1753-1757).

By the nature of his work, Ukhtomsky is quite close to Rastrelli. Both the bell tower of the Lavra and the triumphal gates are rich in external design, monumental and festive. Ukhtomsky’s valuable quality is his desire to develop ensemble solutions. And although his most significant plans were not realized (the project of the ensemble of the Invalid and Hospital Houses in Moscow), the progressive trends in Ukhtomsky’s work were picked up and developed by his great students - Bazhenov and Kazakov.

A prominent place in the architecture of this period was occupied by the work of Savva Ivanovich Chevakinsky (1713-1774/80). A student and successor of Korobov, Chevakinsky participated in the development and implementation of a number of architectural projects in St. Petersburg and Tsarskoe Selo. Chevakinsky's talent was especially fully manifested in the St. Nicholas Naval Cathedral he created (St. Petersburg, 1753 - 1762). The slender four-tiered bell tower of the cathedral is wonderfully designed, enchanting with its festive elegance and impeccable proportions.

Second half of the 18th century. marks a new stage in the history of architecture. Just like other types of art, Russian architecture testifies to the strengthening of the Russian state and the growth of culture, and reflects a new, more sublime idea of \u200b\u200bman. The ideas of citizenship proclaimed by the Enlightenment, the idea of an ideal noble state built on reasonable principles find a unique expression in the aesthetics of classicism of the 18th century, and are reflected in increasingly clear, classically restrained forms of architecture.

Since the 18th century. and until the mid-19th century, Russian architecture occupied one of the leading places in world architecture. Moscow, St. Petersburg and a number of other Russian cities are enriched at this time with first-class ensembles.

The formation of early Russian classicism in architecture is inextricably linked with the names of A. F. Kokorinov, Wallen Delamot, A. Rinaldi, Yu. M. Felten.

Alexander Filippovich Kokorinov (1726-1772) was among the direct assistants of one of the most prominent Russian architects of the mid-18th century. Ukhtomsky. As the latest research shows, the young Kokorinov built the palace ensemble in Petrovsky-Razumovsky (1752-1753), glorified by his contemporaries, which has survived to this day modified and rebuilt. From the point of view of architectural style, this ensemble was undoubtedly close to the magnificent palace buildings of the mid-18th century, erected by Rastrelli and Ukhtomsky. New, foreshadowing the style of Russian classicism, was, in particular, the use of the severe Doric order in the design of the entrance gates of Razumovsky's palace.

Wallen Delamoth. Small Hermitage in Leningrad. 1764-1767

Around 1760, Kokorinov began his many years of joint work with Wallen Delamoth (1729-1800), who came to Russia. Originally from France, Delamote came from a family of famous architects, the Blondels. The name of Wallen Delamoth is associated with such significant buildings in St. Petersburg as the Great Gostiny Dvor (1761 - 1785), the plan of which was developed by Rastrelli, and the Small Hermitage (1764-1767). The Delamot building, known as New Holland, is a building of Admiralty warehouses, where the arch made of simple dark red brick with decorative use of white stone, spanning the canal, attracts special attention with a subtle harmony of architectural forms and solemn and majestic simplicity.

Wallen Delamoth. The central part of the main facade of the Academy of Arts in Leningrad. 1764-1788

A.F. Kokorinov and Wallen Delamoth. Academy of Arts in Leningrad. 1764-1767 View from the Neva.

Wallen Delamoth. "New Holland" in Leningrad. 1770-1779 Arch.

Wallen Delamoth participated in the creation of one of the most unique structures of the 18th century. - Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg (1764-1788). The austere, monumental building of the Academy, built on Vasilyevsky Island, acquired important significance in the city ensemble. The main façade facing the Neva is majestically and calmly designed. The general design of this building indicates the predominance of the style of early classicism over baroque elements.

What is most striking is the plan of this structure, which was apparently mainly developed by Kokorinov. Behind the outwardly calm facades of the building, which occupies an entire city block, hides a complex internal system of educational, residential and utility rooms, stairs and corridors, courtyards and passages. Particularly noteworthy is the layout of the Academy's courtyards, which included one huge round courtyard in the center and four smaller courtyards, rectangular in plan, with two corners rounded in each.

A. F. Kokorinov, Wallen Delamoth. Academy of Arts in Leningrad. Plan.

A building close to the art of early classicism is the Marble Palace (1768-1785). Its author was the Yang architect Antonio Rinaldi (c. 1710-1794), who was invited to Russia. In Rinaldi's earlier buildings, the features of the late Baroque and Rococo style were clearly visible (the latter is especially noticeable in the refined decoration of the apartments of the Chinese Palace in Oranienbaum).

Along with large palace and park ensembles, estate architecture is becoming increasingly developed in Russia. Particularly active construction of estates began in the second half of the 18th century, when Peter III issued a decree exempting nobles from compulsory public service. The Russian nobles, who had dispersed to their ancestral and newly acquired estates, began to intensively build and improve their landscaping, inviting the most prominent architects for this, as well as making extensive use of the labor of talented serf architects. Estate construction reached its greatest prosperity at the end of the 18th - beginning of the 19th century.

Lattice of the Summer Garden in Leningrad. 1773-1784 Attributed to Yu. M. Felten.

The master of early classicism was Yuri Matveevich Felten (1730-1801), one of the creators of the remarkable Neva embankments associated with the implementation of urban planning work in the 1760-1770s. The construction of the lattice of the Summer Garden, in the design of which Felten participated, is also closely connected with the ensemble of Neva embankments. Among the buildings of Velten, the building of the Old Hermitage should be mentioned.

Laundry Bridge over the Fontanka River in Leningrad. 1780s

In the second half of the 18th century. one of the greatest Russian architects, Vasily Ivanovich Bazhenov (1738-1799), lived and worked. Bazhenov was born into the family of a sexton near Moscow, near Maloyaroslavets. At the age of fifteen, Bazhenov was part of a team of painters during the construction of one of the palaces, where he was noticed by the architect Ukhtomsky, who accepted the gifted young man into his “architectural team.” After the organization of the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, Bazhenov was sent there from Moscow, where he studied at the gymnasium at Moscow University. In 1760, Bazhenov went abroad as a pensioner of the Academy, to France and Italy. The outstanding natural talent of the young architect already in those years received high recognition. Twenty-eight-year-old Bazhenov came from abroad with the title of professor of the Roman Academy and the title of academician of the Florence and Bologna Academies.

Bazhenov’s exceptional talent as an architect and his great creative scope were especially clearly manifested in the project of the Kremlin Palace in Moscow, on which he began working in 1767, actually planning the creation of a new Kremlin ensemble.

V.I. Bazhenov. Plan of the Kremlin Palace in Moscow.

According to Bazhenov’s project, the Kremlin was to become, in the full sense of the word, the new center of the ancient Russian capital, and moreover, it would be most directly connected with the city. In anticipation of this project, Bazhenov even intended to tear down part of the Kremlin wall from the side of the Moscow River and Red Square. Thus, the newly created ensemble of several squares in the Kremlin and, first of all, the new Kremlin Palace would no longer be separated from the city.

The façade of Bazhenov’s Kremlin Palace was supposed to be facing the Moscow River, to which ceremonial staircase descents, decorated with monumental and decorative sculpture, led from above, from the Kremlin hill.

The palace building was designed to have four floors, with the first two floors having service purposes, and the third and fourth floors housing the palace apartments themselves with large double-height halls.

V.I. Bazhenov. Project of the Grand Kremlin Palace in Moscow. Incision.

In the architectural design of the Kremlin Palace, new squares, as well as the most significant interior spaces, an exceptionally large role was given to colonnades (mainly of the Ionic and Corinthian orders). In particular, a whole system of colonnades surrounded the main square in the Kremlin designed by Bazhenov. The architect intended to surround this square, which had an oval shape, with buildings with strongly protruding basement parts, forming, as it were, stepped stands to accommodate people.

V. I. Bazhenov. Model of the Kremlin Palace. Fragment of the main facade. 1769-1772 Moscow, Museum of Architecture.

Extensive preparatory work began; in a specially built house, a wonderful (preserved to this day) model of the future structure was made; Bazhenov carefully developed and designed the interior decoration and decoration of the palace...

The unsuspecting architect was in for a cruel blow: as it turned out later, Catherine II did not intend to complete this grandiose construction; she started it mainly with the aim of demonstrating the power and wealth of the state during the Russian-Turkish war. Already in 1775, construction stopped completely.

In subsequent years, Bazhenov’s largest work was the design and construction of an ensemble in Tsaritsyn near Moscow, which was supposed to be the summer residence of Catherine II. The ensemble in Tsaritsyn is a country estate with an asymmetrical arrangement of buildings, executed in a distinctive style, sometimes called “Russian Gothic,” but to a certain extent based on the use of motifs from Russian architecture of the 17th century.

It is in the traditions of ancient Russian architecture that Bazhenov combines the red brick walls of Tsaritsyn buildings with details made of white stone.

The surviving Bazhenov buildings in Tsaritsyn - the Opera House, the Figured Gate, the bridge across the road - give only a partial idea of the general plan. Not only was Bazhenov’s project not implemented, but even the palace he had almost completed was rejected by the visiting empress and, on her orders, demolished.

V. I. Bazhenov. Pavilions of the Mikhailovsky (Engineering) Castle in Leningrad. 1797-1800

V. I. Bazhenov. Mikhailovsky (Engineering) Castle in Leningrad. 1797-1800 Northern façade.

Bazhenov paid tribute to the emerging pre-romantic tendencies in the project of the Mikhailovsky (Engineers) Castle, which, with some changes, was carried out by the architect V. F. Brenna. Built by order of Paul I in St. Petersburg, Mikhailovsky Castle (1797-1800) was at that time a structure surrounded, like a fortress, by ditches; drawbridges were thrown across them. The tectonic clarity of the general architectural design and at the same time the complexity of the layout were combined here in a unique way.

In most of his projects and structures, Bazhenov acted as the greatest master of early Russian classicism. A remarkable creation of Bazhenov is the Pashkov House in Moscow (now the old building of the State Library named after V. I. Lenin). This building was built in 1784-1787. A palace-type structure, the Pashkov House (named after the first owner) turned out to be so perfect that both from the point of view of the urban ensemble and in terms of its high artistic merits, it took one of the first places among the monuments of Russian architecture.

V. I. Bazhenov. House of P.E. Pashkov in Moscow. 1784-1787 Main facade.

The main entrance to the building was located from the front yard, where several service buildings of the palace-estate were located. Situated on a hill rising from Mokhovaya Street, Pashkov’s house faces its main façade towards the Kremlin. The main architectural mass of the palace is its central three-story building, topped with a light belvedere. There are two side two-story buildings on both sides of the building. The central building of Pashkov's house is decorated with a Corinthian order colonnade, connecting the second and third floors. The side pavilions have smooth columns of the Ionic order. The subtle thoughtfulness of the overall composition and all the details gives this structure extraordinary lightness and at the same time significance and monumentality. The true harmony of the whole, the grace of the elaboration of details eloquently testify to the genius of its creator.

Another great Russian architect who worked at one time with Bazhenov was Matvey Fedorovich Kazakov (1738-1812). A native of Moscow, Kazakov connected his creative activity even more closely than Bazhenov with Moscow architecture. Having entered the Ukhtomsky school at the age of thirteen, Kazakov learned the art of architecture in practice. He was neither at the Academy of Arts nor abroad. From the first half of the 1760s. young Kazakov was already working in Tver, where a number of buildings for both residential and public purposes were built according to his design.

In 1767, Kazakov was invited by Bazhenov as his direct assistant to design the ensemble of the new Kremlin Palace.

M.F.Kazakov.Senate in the Moscow Kremlin. Plan.

M. F. Kazakov. Senate in the Moscow Kremlin. 1776-1787 Main facade.

One of the earliest and at the same time the most significant and famous buildings of Kazakov is the Senate building in Moscow (1776-1787). The Senate building (currently the Supreme Soviet of the USSR is located here) is located inside the Kremlin not far from the Arsenal. Triangular in plan (with courtyards), one of its facades faces Red Square. The central compositional unit of the building is the Senate hall, which has a huge domed ceiling for that time, the diameter of which reaches almost 25 m. The relatively modest design of the building from the outside is contrasted with the magnificent design of the round main hall, which has three tiers of windows, a Corinthian order colonnade, a coffered dome and a rich stucco.

The next widely known creation of Kazakov is the building of Moscow University (1786-1793). This time, Kazakov turned to the common plan of a city estate in the form of the letter P. In the center of the building there is an assembly hall in the shape of a semi-rotunda with a domed ceiling. The original appearance of the university, built by Kazakov, differs significantly from the external design given to it by D.I. Gilardi, who restored the university after the fire of Moscow in 1812. The Doric colonnade, reliefs and pediment above the portico, aedicules at the ends of the side wings, etc. - all this was not in Kazakov’s building. It looked taller and less spread out along the façade. The main facade of the university in the 18th century. had a more slender and lighter colonnade of the portico (Ionic order), the walls of the building were divided by blades and panels, the ends of the side wings of the building had Ionic porticoes with four pilasters and a pediment.

Like Bazhenov, Kazakov sometimes turned in his work to the architectural traditions of Ancient Rus', for example in the Petrovsky Palace, built in 1775-1782. Jug-shaped columns, arches, window decorations, hanging weights, etc., together with red brick walls and white stone decorations, clearly echoed pre-Petrine architecture.

However, most of Kazakov’s church buildings - the Church of Philip Metropolitan, the Church of the Ascension on Gorokhovskaya Street (now Kazakova Street) in Moscow, the church-mausoleum of Baryshnikov (in the village of Nikolo-Pogoreloye, Smolensk region) - were decided not so much in terms of ancient Russian churches, but in the spirit classically torus

Architecture XVII century

Abstract >> Construction« Architecture XVII century"XVII century appeared century shocks and huge changes in Russia. This century turmoil, ... the life-affirming character of the rapidly developing Russian national art XVII c.Proper Russian architecture XVII V. desire for pomp...

Russian culture 18 century

Abstract >> Culture and artFuture revolution. Chapter 3. Architecture. The dynamics of stylistic development are also growing in a peculiar way. Russian architecture XVIII century. In the country, belatedly... and colorful embroideries. Throughout XVIII century Russian the art of painting has come a long way...

Russian portrait XVIII century

Abstract >> Culture and artExpressions. And in architecture, and in sculpture, and in painting, and in graphics Russian art reached pan-European... XVIII century there was no sculptural portrait. Peculiarities Russian portrait of the middle XVIII century From the middle XVII in the middle XVIII century ...

Russian culture XVII century

Abstract >> Culture and artShort review Russian history from ancient times to the 70s. XVII century, - “Synopsis” of Innocent... - Karion Istomin, Sylvester Medvedev. Architecture. In development architecture XVII V. Three stages can be distinguished: 1) first...

-

Published: November 14, 2013 Architecture of Moscow 18th century

Alekseev F. Ya. Cathedral Square in the Moscow Kremlin 1811 - Moscow Architecture of the 18th centuryAlready in the 18th century, in Moscow architecture one could see buildings that simultaneously combined the features of both Russian and Western culture, imprinting the Middle Ages and Modern Times in one place. By the beginning of the 18th century, at the intersection of Zemlyanoy Val and Sretenka Street, a building appeared near the gate of Streletskaya Sloboda, the architect Mikhail Ivanovich Choglokov contributed to this. Once upon a time, Sukharev’s regiment was stationed here, which is why the tower was named in memory of the colonel, that is Sukhareva.

Sukharevskaya Tower, designed by M.I. Choglokov (was built in 1692-1695 on the site of the old wooden Sretensky Gate of the Zemlyanoy City (at the intersection of the Garden Ring and Sretenka Street). In 1698-1701 the gate was rebuilt in the form in which they survived until the beginning of the 20th century, with a tall tower topped with a tent in the center, reminiscent of a Western European town hall.

The tower changed its appearance enormously in 1701, after reconstruction. It now has more details reminiscent of medieval Western European cathedrals, namely clocks and turrets. In it, Peter I established a school of mathematical and navigational sciences, and an observatory appeared here. But in 1934 the Sukharev Tower was destroyed so as not to interfere with traffic.

During the same period, churches in the Western European style were actively built in the capital and region (the estate of Dubrovitsy and Ubory). In 1704, Menshikov A.D. gave an order to the architect I.P. Zarudny for the construction of the Church of the Archangel Gabriel near the Myasnitsky Gate, otherwise known as the Menshikov Tower. Its distinctive feature is a tall, wide bell tower in the Baroque style.

Dmitry Vasilyevich Ukhtomsky made his contribution to the development of the capital's architecture; he created great creations: the bell tower of the Trinity-Sergius Monastery and the Red Gate in Moscow. Previously, there was already a bell tower here, but Ukhtomsky added two new tiers to it, now there are five of them and the height has reached 80 meters. Bells could not be placed on the upper tiers due to the fragility of the structure, but they added grace and solemnity to the building, which was now visible from different parts of the city.

Red Gate, Unfortunately, now they can only be seen in pictures of textbooks; they have not survived to this day, but they are deservedly the best architectural structures of the Russian Baroque. The way they were built and modified is directly related to the history of life in Moscow in the 18th century. and indicatively characterizes that era. When the Russians won the Battle of Poltava against the Swedish army in 1709, a triumphal wooden gate appeared on Myasnitskaya Street. In the same place, on the occasion of the coronation of Elizabeth Petrovna in 1742, a second gate was built, funds for this were allocated by the local merchants. They stood for a short time before they burned, but Elizabeth immediately ordered them to be restored in stone; this work was entrusted to Ukhtomsky, who was mentioned earlier.

The gate was made like an ancient Roman triumphal arch; the residents of the capital loved it very much, which is why they called it Red, from the word “beautiful”. Initially, the building ended with a graceful tent, on which was a figure of trumpeting Glory with a palm branch. A portrait of Elizabeth was placed above the aisle, which was eventually decorated with a medallion with a coat of arms and monograms. On the sides, above additional passages, there are reliefs in honor of the empress, and above them there are also statues as symbols of Vigilance, Grace, Constancy, Loyalty, Trade, Economy, Abundance and Courage. About 50 different images were painted on the gate. When the Square was reconstructed in 1928, this great structure was mercilessly dismantled; now there is an ordinary gray metro pavilion, associated with a completely different time.

They stopped talking about the Peter the Great era now that the architects had finally completed the construction of St. Petersburg, which became the capital. Moving towards the end of the 18th century, again all construction returned to Moscow. They began to actively build secular houses and palaces, churches, educational and medical institutions. The best architects of the times of Catherine II and Paul I were Kazakov and Bazhenov.

Bazhenov Vasily Ivanovich studied at the gymnasium at Moscow University, and then at the new St. Petersburg Academy of Arts. When he completed his studies, he went to explore Italy and France, and then returned to St. Petersburg, where he was awarded the title of academician. Although Bazhenov’s career in St. Petersburg was very successful, he still went to Moscow to bring to life the project of Catherine II - the Grand Kremlin Palace. Patriarchal Moscow could not accept such a project; it stood out too much from the general picture of that time.

Alekseev F. Ya. View of the Moscow Kremlin from the side of the Stone Bridge 1811

It was planned to half demolish the southern walls of the Kremlin, obsolete buildings, and around what remained - the oldest cultural monuments, churches and bell towers, to erect a new pompous palace building in the style of classicism. Bazhenov wanted to build not only one palace, but also to have a theater, an arsenal, colleges, and a square for the people nearby. The Kremlin was not supposed to become a medieval fortress, but a large public place for the city and its inhabitants. The architect presented first of all the drawings of the future palace, and then its wooden model. This model was sent to Catherine II in St. Petersburg for her approval, and then left in the Winter Palace. The project was approved, even the first stone was solemnly laid with the participation of the Empress, but it was never completed.

In 1775, Catherine II gave a new order to Bazhenov to build a personal residence near Moscow on the Tsaritsyno estate, which at that time was called Black Mud. The Empress wanted the building to be built in a pseudo-Gothic style. Since 1775, the famous Grand Palace, the Bread House, the Opera House, stone bridges and much more were built, which can still be seen today.

Alekseev F. Ya. Panoramic view of Tsaritsyno 1800

The Tsaritsyn ensemble was very different from the estates of that time; they had a large number of elements of Gothic architecture, for example, pointed arches, window openings of complex shape, etc. Bazhenov said that Old Russian architecture is a subtype of Gothic, so there were also elements of the Russian Middle Ages, such as the forked battlements at the top, similar to the end of the Kremlin walls. A characteristic feature of Russian architecture was the combination of white stone details and red brick walls. Inside, everything was specially complicated in a medieval style. The palace looked very rough and gloomy, and when the empress came to look at it, she said with horror that the palace was more like a prison, and never returned there again. She ordered the palace to be demolished, along with some other buildings. The task was transferred to another architect - Kazakov M.F., who preserved the classicist correct shape of the building and made a Gothic design.

Pashkov House, architect Bazhenov

Many other buildings were also ordered from Bazhenov. For example, his work was the house of P.E. Pashkov, which faces the Kremlin; it is distinguished by its classic style, light facade, brick walls, which further emphasize the power and majesty of the building. The house is located on a hill, in the middle there is a 3-storey house with a neat portico, statues rise on the sides, and at the top there is a round sculptural composition of the belvedere. The galleries are made on one floor, which are continued by two-story wings with porticoes. From the hill you can go down the stairs, at first it led to a garden with beautiful fences and lanterns, but by the 20th century the street was widened and there were no trellises or garden left. M. F. Kazakov would not have been able to create to such an extent without the influence of Bazhenov and Ukhtomsky. Catherine II liked Kazakov’s work, and she trusted him with more than one commission, including houses for living, palaces for the royal family, churches in the style of classicism.

Petrovsky travel (access) palace on the Tverskoy tract, architect Kazakov

On the way from St. Petersburg to Moscow, one could stop at the Petrovsky Access Palace, otherwise it was called the Petrovsky Castle, Kazakov also worked on it and used a pseudo-Gothic style. But still, classicism could not be avoided; the correct symmetrical shapes of the rooms and all the interior design speak about it. Only by the elements of the facade could one recognize the echoes of ancient Russian culture.

The next building, the construction of which began in 1776 and was completed in 1787, was again done with the help of Kazakov, this was the Senate in the Moscow Kremlin. The building is fully consistent with the traditions of classicism, but it also reflects the features of Bazhenov’s Kremlin restructuring project. The main part of the building is triangular; in the middle there is a large round hall with a large dome, which cannot be missed while on Red Square. Bazhenov and his colleagues had great doubts about the strength of the dome, and to refute this, Kazakov himself climbed onto it and stood motionless for half an hour. On the front side of the building there is a colonnade that emphasizes the smooth curves of the walls.

An equally significant event was the organization of the graceful Hall of Columns in the house of the Noble Assembly in Moscow; Kazakov was responsible for its design at the end of the 18th century. The area of the building is of a regular rectangular shape; columns are placed along the perimeter, which do not stand directly under the walls, but at some distance. Crystal chandeliers hang along the entire perimeter; the upper mezzanine is surrounded by a fence of figured posts connected by railings. The proportions are strictly observed, which does not allow you to take your eyes off.

Alekseev F. Ya. Strastnaya Square (Triumphal Gate, Church of St. Demetrius of Thessaloniki and Kozitskaya’s House), painting 1800.

In the center of the capital, Kazakov built a university, right on Mokhovaya Street, this happened in 1789-1793. A couple of decades later, the building burned down, but was partially restored by the architect Domenico Gilardi; he did not make any fundamental changes, but left the Cossack principle in the form of the letter “P” and the general plan of the composition.

Moscow University, 1798, architect Matvey Kazakov

Kazakov was very surprised by the fire that happened; the news came to him in Ryazan. He could not bear such a blow and soon died; he was informed that the fire had consumed all his buildings. But in fact, many buildings have survived to this day, from which one can immediately see the commonality of the architecture of the 18th century - “Cossack Moscow”.

In the middle of the 18th century. In the northern part of the territory of the modern Neskuchny Garden, an estate arose, ordered by P. A. Demidov, the son of a Ural breeder and a famous amateur gardener.

In 1756 The main house was built - U-shaped chambers in plan - the Alexandria Palace. A balcony on columns was placed between the projections of the garden facade. The courtyard in front of the house was surrounded by stone services and a cast-iron fence, cast at Demidov's factories.

Alekseev F. Ya. Military hospital in Lefortovo 1800

Alekseev F. Ya. View of the Church "St. Nicholas the Great Cross" on Ilyinka 1800

Alekseev F. Ya. View of the church behind the Golden Lattice and the Terem Palace 1811

Alekseev F. Ya. View in the Kremlin of the Senate, Arsenal and Nikolsky Gate, painting 1800 G.

article in preparation

Architecture of Russia 16th century Arbat Street, Moscow (architecture, history) Povarskaya street, Moscow (architecture, history) Kuznetsky Most Street, Moscow (history, architecture) Lianozovo district, Moscow, history Moscow architecture, monuments, history, modern capital Architecture of Russia and Moscow, modernity, 19th, 18th, 17th centuries, early periods (13th-16th centuries) Kievan Rus (9th-13th centuries) Architectural style Sights of Moscow (Iveron Gate, 18th century, painting by Vasnetsov)

After the end of the era of Peter the Great, during which the forces of all the best Russian architects were thrown into the construction of a new capital, St. Petersburg, they again took up the reconstruction and construction of Moscow. At this time, churches and hospitals, schools and universities, as well as various public buildings grew up right before our eyes.

Among the most prominent architects of the mid-18th century were M. Kazakov and V. Bazhenov. In 1799, V. Bazhenov graduated from the gymnasium, which was located at Moscow University, then continued his studies at the new, newly organized Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg. After completing his studies, Bazhenov goes to Italy and France, and upon his return, he receives the title of academician.

(Kremlin Palace within the white walls of the Kremlin)

Not paying attention to the fact that his architectural career in the capital was developing in the best way, Bazhenov, at the invitation of Catherine II, returned to Moscow, where he began to implement the empress’s grandiose plans, and first of all, the construction of the Kremlin Palace. But as it turned out, patriarchal Moscow was not yet ready for the architect’s too bold decisions, and his project failed miserably.

(White Kremlin)

By order of the Empress, it was necessary to demolish the most dilapidated buildings of the Kremlin, dismantle some sections of the walls on the southern side, and build a grandiose palace in the style of classicism around the remaining ancient buildings, including the Ivan the Great bell tower. Following the architect's plans, many buildings were erected on the territory of the Kremlin, which included a theater, various colleges, an arsenal, as well as a people's square.

All this was done with the sole purpose of turning the medieval fortress into a large public complex closely connected with the capital. Bazhenov presented Catherine not only with drawings of the future palace, but also made a wooden model of it. But despite the fact that the Empress approved the architect’s project, and even held a ceremony to lay the first stone, it was not destined to be brought to life. At the beginning of 1775, Catherine II gave Bazhenov a new task to build for her, not far from Moscow, a residence on the territory of the Black Mud estate, which later became known as Tsaritsyno.

(Palace in Tsaritsino)

At the request of the empress, this complex was built in a pseudo-Gothic style. By the end of 1785, stone bridges, the Grand Palace, the Opera House and the Bread House, as well as many other structures, were built, most of which have survived to this day. The Tsaritsyno complex differed from the building ensembles of that time in its forms of architecture, made in the Gothic style. First of all, it stood out for its complex design of window openings, pointed arches and similar unusual elements.

(Vasilevsky descent)

Here you can also find native Russian elements of medieval architecture, for example the “Swallow’s Tail”, reminiscent of the ends of the walls of the modern Kremlin. The walls, made of red brick, are perfectly combined with white decorative elements; this combination is inherent in the architecture of the late 17th century. As for the layout, it was deliberately made as complex as possible. From the outside, the palace looked so gloomy that when the empress saw it, she exclaimed that it looked more like a prison and not like the queen’s residence.

(Moscow Kremlin of the 18th century)

She refused to live there. Subsequently, by order of the empress, most of the buildings, which included the palace, were demolished. The construction of the new palace, in the Gothic style, was entrusted to the then famous Russian architect M. Kazakov. He completed its construction by the end of 1793.