Elbrus is a great attraction for all skiers who have been to the Central Caucasus region. Its peaks are clearly visible - both Western and Eastern - two dominant snow-ice giants that determine the beauty of the surrounding landscape. All the couloirs, all the ice fields and all the snowfields are visible. There are practically no particularly cool places, and of course you can find “No fall zone”, but you have to try really hard. It would seem that everything is simple - you dress warmly so that the piercing cold wind does not get under your jacket, you get up early so as not to go down the muddy “porridge” and to return back to lunch, and forward - up, with your feet to any of the peaks. A desired goal, sitting securely in the subconscious, just a stone's throw away.

However, however, however... climbing Elbrus is not as simple as it seems from afar, this route is complicated by many factors and can be completed only when you are very “lucky”.

In July 2000, a group of Russian skiers successfully climbed the Northern slope of Elbrus to the Eastern peak and descended from there to alpine skiing. According to the Caucasian Mountain Society, this was the first reliably recorded ski descent on the Northern slopes of Russian skiers. Last year, a similar route, slightly different from ours, was completed by the Americans, the team of Warren Miller. Our group included: Evgeny Lyubimov, Alexander Zakharov, Nikolay Veselovsky (Moscow), Igor Komarov (Pyatigorsk), Ilya Gavrilov (Kislovodsk).

The first day. Road

We left Kislovodsk late, around two in the afternoon, since organizational issues took up a lot of time: food, car, loading and unloading... The road from the city to the foot of Elbrus, meandering along the plain, gradually turns into the foothills and, crossing the Podkumok River, turns into "primer". A fairly good “dirt road” winds like a serpentine through the mountains, climbing steep climbs and sliding down steep descents. After some time we leave for the pass. From here Elbrus is in full view. The weather is good, and the view of Elbrus is completely incomparable to what is usually visible from the Baksan Gorge. The mountain is visible from top to bottom, there are no large peaks around, so the feeling is absolutely amazing - it seems that the snow caps are hanging in the air and all this bulk does not overwhelm, but evokes a feeling of some kind of lightness and happiness. One of the names of Elbrus is “Shat-geri” - “Mountain of Happiness”.Further the road becomes more fun. Actually, the very reminder of the road ends and something similar to goat trails begins. There are actually stones constantly “going” from above and the roadbed of this road also has a slight slope towards the valley. The turns are so short that the car doesn’t always fit into them the first time, and this is where the fun begins: it feels like for the guys from the Ministry of Emergency Situations driving their cars along these roads, “Camel Trophy” is just a constant, daily job. Having passed two fords across rivers, a couple of passes, one of which is already at an altitude of 1800 m, our car, having overcome the last dizzying descent, entered the Surkh valley.

The Surkh glade is a huge plane about two kilometers long and a kilometer wide, along which the Malka River flows. On all sides this space is a zone alpine meadows- surrounded by mountains, so there is no wind and the weather is usually good. We pass by a memorial sign located on the spot where General Emmanuel's expedition stood and after which the final ford across Malka begins. The car drives into a mountain river and travels about a hundred meters along the river flow. The feeling is as if you are participating in rafting in a GAZ-66 car. Our driver, Lesha, is apparently an experienced “raftsman” and knows well the peculiarities of driving a car along mountain rivers, so this adventure of ours ends happily. We drive out to the opposite bank and here an amazing picture opens up to us - a green clearing, on which a dozen colorful tents and a large rescue service tent have settled like butterflies. The guys from the rescue services accommodate us in their tent, since we go up in the morning.

Second day

We get up in the morning. Even in Kislovodsk, I was amazed by the amount of cargo that we have to lift up and which is necessary for a successful climb to the top. I understand that we cannot carry all this myriad of different backpacks and packages to the foot of Elbrus in one day. We take personal equipment: skis, boots, sleeping bags, one tent, some food, everything is minimal, but as a result the backpack still turns out to be too heavy to carry. We leave around nine o'clock in the morning. First, the road goes through the area of alpine meadows. Amazing variety of herbs and flowers. At the beginning you try to walk around all these beauties and not step on the blooming and fragrant rhododendrons, but after three hours it becomes very tiring and you already go where it is easier to go. Hot...Gradually the meadow zone ends and huge stone rubble begins. Sometimes you simply had to climb over these rubble using elements of rock-climbing equipment. We climb out onto a rocky ridge, from where Elbrus itself and its glaciers are already visible. The spectacle is truly magnificent - huge cracks, glacial fields. Then the path goes along this very ridge - steep and blown by a piercing wind. It's getting harder and harder to climb the ridge. The weather is getting worse... After a while, a snow squall comes - in fact, it is not snow itself, but snow pellets, similar to foam plastic. The horizon is covered with thunderclouds and the skis that are tied to the back of the backpack begin to hit the back of the head with a spark. We understand that we need to go as quickly as possible. After about six hours of such walking and climbing along the ridge and running away from the thunderstorm, we come out to the moraine, which is located at an altitude of 3,700 m. On this moraine there are a dozen tents, which are blown by the cold wind and where you can already feel the proximity of the cold glaciers of Elbrus.

We put up a tent, throw a load into it and, without waiting for a new thunderstorm charge, quickly drop down. When we went down and looked at the clock, we realized that the transfer took exactly eleven hours. The only strength left was to eat quickly and fall asleep with one thought: “I wonder what will make you go this way again?”

Day three. Camp on the moraine

In the morning we got up, oddly enough, quite cheerfully. I was very pleased that the bulk of the cargo was abandoned yesterday and the backpacks were noticeably lighter. The second transfer took place virtually along the same path as the first - the classic path along which the expedition of General Emmanuel went. Suddenly we realized: on the second day it was much easier to walk - acclimatization was beginning to take its toll, that is, instead of six and a half hours of climbing on the first day, we had already spent five hours on the second day. Almost complete absence of wind and very good weather. Somewhere around three o'clock in the afternoon we went out onto the moraine, set up a second tent and began to settle down in this camp. There were a lot of people - guys from the Caucasian Mountain Society, many thanks to them - they fed us lunch, and at the same time the Greeks, who also camped on the moraine. By evening the weather began to worsen, the sky began to become cloudy and the wind began to blow. With this we went to bed.Day four. Lenz Rocks

In the morning we go out on our first acclimatization trip. We only take skis, some chocolate and water with us. The slope up to the Lenz rocks is covered with a network of cracks, so we go together. The weather is sunny, almost ideal, very warm, completely calm. It must be said that the tactics for climbing Elbrus from the north differ from those used in the south. If in the south you climb to a height of 3800 m along the chain of Elbrus cable cars and acclimatization can be carried out in fairly comfortable conditions of the “barrels” on Gara-Bashi, where there is water, light, heat, and there are practically no drop-offs, then when climbing from the north everything is a little different. The tactics are closer to the Himalayan climbs - with intermediate camps and drop-offs. On the south side, reaching the summit is usually planned for two to three o'clock in the morning, and with good weather and physical preparation, in seven to ten hours you will already be at the top. When climbing Elbrus from the north, almost no one goes out at night, but goes with an intermediate camp on the Lenz rocks, at an altitude of about 4,800 m. Therefore, from the north, access to the mountain usually occurs around nine in the morning. But let's get back to our training exit.We are gradually moving forward. The altitude and lack of acclimatization gradually make themselves felt - breathing is heavy, legs fill with lead. From a height of 4.577 m (lower cliff of Lenz) Zhenya Lyubimov turns back. There is simply no strength to go further... We rise a little higher, to an altitude of 4.659 m - to the so-called “lower overnight stays”. There is a small area here, covered on all sides by rocks, there is water... but the height makes itself felt - at this height Kolya Veselovsky says that he will not go further - the severe traumatic brain injury received by Kolya several years ago in the Elbrus region makes itself felt headaches + a cold picked up somewhere along the way... Kolya understands that the mountain is closed to him...

We descend to the moraine on skis along a fairly gentle snow slope, soggy from the hot sun. About a dozen cracks that can easily be crossed over snow bridges have been marked by the rescue service guys. The only thing: when passing over the cracks, you become weightless and just want to fly up.

Lesha (rescuer) is coming down with us - the same driver who drove the GAZ-66 on the way to the camp and used it as a means of rafting to overcome water obstacles. Added to all of Lesha’s advantages is the fact that he turns out to be a good skier.

We go down and the strength comes just before our eyes, so much so that you are very surprised: where were they when you went up?

Day five. Overnight stays

The weather for the second day was almost perfect - calm, sun... and there was nothing more to wait for - despite insufficient acclimatization, we decided to go up. We take with us a small supply of food, a tent and move to the top, dividing into two groups. In the first are: I, Alexander Zakharov, and Ilya Gavrilov, the commander of the rescuers. In the second group: Igor Komarov and Evgeny Lyubimov. Since yesterday's outing showed that the snow bridges over the cracks are quite solid, we go without being tied up.The same effect appears as on the approaches - on the second day it is much easier to walk, apparently, acclimatization is still being gained with this tactic: going up with skis and quickly descending on them. Around three o'clock in the afternoon we reach a height of 4,804 m. At this point in the Lenz rocks we can set up a small camp, which we do in magnificent calm weather. Taking off our shoes, we walk barefoot. Ilya, looking thoughtfully at all this “bliss,” says that such weather happens here ten days a year. And confirmation of this is the fact that just a few days ago the guys from the Ministry of Emergency Situations were forced to spend the night in this place, and a strong south wind tore their tent to shreds, providing a “cold” overnight stay. Therefore, listening to Ilya, I understand that we are really very lucky.

After dinner and talking about life, we went to bed around ten o’clock. It must be said that there is practically no sleep at this altitude, but FM radio stations from the city of Kislovodsk are excellently received. Therefore, almost all night I lie with a radio player, with headphones and listen to music. By the morning, it seems that I had fallen asleep a little, because I was woken up by the voices of two people, apparently veterans of Soviet mountaineering - one about fifty years old, the other about sixty, who settled in the next tent and actually live at this altitude. They really like it here and go to different peaks of Elbrus every day. Moreover, on the previous day, two peaks were not enough for one of them - he first went to the Eastern one, then to the Western one, and since there was still time left, he went to the Eastern one again and went down. He walks in felt boots to which the “cats” are tied, so he leaves footprints on the mountain similar to those of a bear - a large “bast shoe” with marks from “claws”.

From the Lenz rocks the path goes up along a couloir sandwiched between two rock ridges. We go to the top in the same order as yesterday: I follow Ilya, Igor and Zhenya follow us. We go along the right side of the couloir. The first hundred meters are very difficult - so difficult that doubt arises: will I reach the top, although it is very close, clearly visible. After a hundred meters we “disperse” and then it’s easier to walk. Following Ilya is a real pleasure - an excellent guide, good pace, good stride, very competent choice of route, we keep pace. Such a movement has meditative properties, and after a while you fall into prostration, when time and space simply disappear, and you just walk, just walk, thinking about something - which, in fact, you don’t even know about.

After some time we go to the top of the Lenz rocks. The height is 5.183 m - almost the height of the Elbrus saddle. We stop here for a smoke break. Ilya lazily lights up “Our Brand”, sitting in the rocks, the weather is good, there is no wind. The rescue commander smokes so “deliciously” that looking at him, you want to smoke yourself, but I understand that it’s better to leave this pleasure a little for later - there’s not enough oxygen here anyway.

Rescuers approach from below - Danila, “Doctor”, “Titanic”. They drag up a radio repeater, which, together with solar battery they want to install it on the top of Elbrus.

We rested for quite a long time, probably about twenty minutes, and waited for Zhenya and Igor to arrive. After a while they come out onto the rocks - Zhenya looks very tired. As a matter of fact, at such a height there are no cheerful people at all, and “very tired” is also a bit of a wrong phrase. But the top is already very close, it feels like another fifteen minutes and you’re already at the top. But in fact, it’s still two hours away, Zhenya doesn’t know this, and that’s very good. Ilya unloads it, takes Zhenya’s skis and we go up to the top. Igor and Zhenya continue to rest.

The weather is magnificent - Kazbek is clearly visible in the east, a little westerly breeze is blowing...

Somewhere a hundred meters before the top, the altitude begins to take its toll very much - I lose pace and fall behind Ilya. In such a situation, it is better not to stop and it is better to just slow down and go slower. I can already see that Ilya has stepped onto the rim of the crater. At 11 o’clock I also go out to the rim of the crater, spending a total of about four hours on the climb. Height 5.584 m

Ilya and the rescuers climb the rock that closes the crater to install a repeater there, and I decided to cross the crater in a straight line to go directly to the top. The summit sign of the Eastern Peak is very clearly visible from here - a stainless steel pyramid that glistens in the sun and is visible from afar.

While crossing the crater, at some point my right leg fell through, and the first thought that came to my mind was: “Where is there a snowdrift here?!” The next moment the second leg falls through and I fall waist-deep into a crack. Suddenly energy appears and I very quickly jump out of there, using special handles of sticks with “beaks”. I don’t risk it any further - I go out to the ridge and walk on the pebbles. I go to the top of Elbrus and here the sight is completely unusual - the first thing I see is a flag Air Force and several guys in airborne blue berets who are photographed against the background of this flag. It turns out that at that time the military “Elbrusiad” was taking place on the southern side and therefore there were quite a lot of people on the top of Elbrus. It was the first time I saw such “crowded people” at the top. An absolutely amazing meeting: Misha Kalinkin, my old friend, a bard famous for his “ski” songs, climbed Elbrus from the south at the same time as us, and here, in the very center of the Caucasus, at an altitude of more than 5,000 meters, we met him .

After taking a few photos, I put on my skis and begin the descent. Starting from the very summit mark, I cross the crater in a straight line, being careful of the cracks. On the opposite side of the crater there is a counterslope, along which I accelerate even more - the gained speed allows me to reach the edge of the crater. At this time I see that Zhenya Lyubimov and Igor Komarov are coming out onto the crater rim. Still, they got there and now there are three of us!

After resting a bit, we put on our skis and begin the descent. In the upper part, the descent follows almost the same path as the ascent. The slope is about twenty degrees steep, covered with sastrugi, so you have to drive very carefully all the time, choosing a road and going around these sastrugi. Out of the corner of my eye I see a group of climbers from the Caucasian Mountain Society climbing. You notice in those eyes, which still express something at such a height, enormous envy of the person skiing. It takes me a few minutes to get to camp, but for them it’s a hard climb up, and then an even harder descent down.

After some time, along a narrow passage literally the width of a ski, we enter a couloir between two rocky ridges. Last year, the Americans either didn’t find this approach, or didn’t get there, but they went out onto the slope lying to the left of the Lenz rocks and ended up in the zone of ice faults and cracks, and the descent, apparently, was quite problematic, stressful and associated with great risk.

The path we chose was more natural, safer and, to some extent, more picturesque, because we descended along a couloir a hundred to two hundred meters wide, sandwiched between two rocky ridges, and did not make our way “by touch” between cracks.

Along the descent line we reach the place of the previous night. Further rocky faults begin, so you have to turn left and leave the Lenz rocks into an open area. Here you need to drive much more carefully, as you can stumble upon cracks along the way. Igor and Zhenya stop to take off their Gore-Tex jackets, since it is already getting quite hot in the lower part. I don’t stop to preserve the whole impression of the descent.

The slope gradually becomes softer, the sastrugi become smaller, and after the Lenz rocks it turns into huge fields acidic firn, sliding on which is a real pleasure. The steepness here decreases somewhat and the only thing that still keeps you in suspense is the cracks along the way. Interestingly, over the past two days the weather has been quite warm and even more cracks have opened up from under the snow, which we did not see on the way up. You have to drive very carefully, constantly looking far ahead. You have to cross snow bridges while “unloading” your skis, so as not to collapse the melted and sagging snow bridges.

After a while I drive up to our moraine, turn to look at my trail and see Igor and Zhenya drawing magnificent, kilometer-long rounded “figure eights” on the soft slope. The spectacle is very beautiful and truly unusual for these places. That's it, we're down!

Day six. Polyana Surkh

At night there was a strong storm wind. The feeling is that several people are standing outside and shaking the tent with you and what is in it. Despite this “carousel”, I slept absolutely wonderfully, since the fatigue and lack of sleep of the previous days took its toll.We went downstairs already quite exhausted. But what was our surprise and pleasure when, entering the rescue tent, we saw Lesha greeting us there with a set table and a huge pot of borscht. It's nice that the guys were waiting for us...

In the evening there was a kind of rewarding ceremony for the participants. We sat by the fire and sang songs...

Day seven

In the morning we quickly and organizedly broke up the camp. The garbage was burned and two hours later there was nothing to indicate that there had once been a camp and people in this clearing. We load into the car and leave.After fording through Malka, we climb by car to the pass and take a last look at the Surkh clearing. The mountain accepted and the mountain let go... Thank you.

A few words about inventory:

We used freeride skis:

- Salomon X-Scream Series

- Salomon AK Rockets

- Fischer Alltrax Freeride

- K2 El Kamino

Boots:

- Salomon X-Scream

- Salomon Force 9

- Salomon SX 92 is a fairly old model, but personally I find them good and easy to fit into. You don’t need to warm them up in your sleeping bag so you can get into them in the morning. In addition, the absence of a tongue in the inner boot makes the SX-92 very comfortable when climbing - you won’t chafe your shin.

We tracked all the coordinates and the route using the GPS Magellan satellite orientation system. The thing is very convenient, significantly increasing the safety of the route.

In conclusion, I would like to thank Salomon, in particular Maxim Ivanov, for providing skis, a tent and some of the equipment for the expedition. Many thanks to the rescuers of the Kislovodsk Ministry of Emergency Situations. These guys helped us in delivering cargo, in arranging and setting up the camp, and helped us on the descent. Thank you! I call people as they are usually called on the mountain: Commander, Lekha, Titanic, Doc, Danila, Old, thank you again!

Special huge thanks to the leadership of the Caucasian Mountain Society, which helped us in organizing our expedition and sheltered us in their camp. I would especially like to mention N.I. Matienko and E.V. Zaporozhchenko.

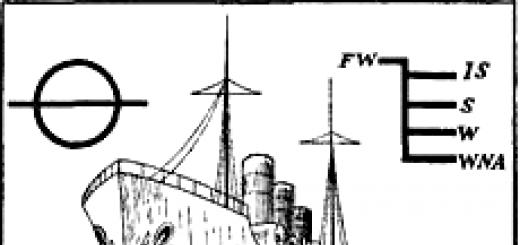

The actual ascent to the top of Elbrus from the north usually starts from Northern shelter(3700). First, climb along the glacier to the Lenz rocks (approx. 4500). Depending on the conditions, it can be either open ice or a glacier covered with snow. In spring and especially in winter - areas of "bottle" winter ice, very hard. It is difficult to get crampons into such ice and tighten ice screws. In our case, there was dense, wind-blown snow with patches of ice. Starting from an altitude of 3900 and up to the beginning of the Lenz rocks (L1), there is a zone of cracks; you should definitely walk in bundles.3700 - Northern shelter (Lakkolit and EMERCOM), L1 - lower cliffs of Lenz, L2 - Middle cliffs of Lenz, arrow - "helipad"

The green line is a traverse to the saddle; the saddle itself is not visible.

The classic option for climbing the Eastern peak of Elbrus from the north is straight up through Lenz rocks. The Lenz rocks are several rock ridges stretching in parallel to approximately an altitude of 5200. The height of individual rocks is up to 10 meters. From the lower cliffs of Lenz (L1, 4500) you should climb to the right of the rock ridge to Sredniye Skal (L2, 4800). There is a wide platform there, called a helicopter platform - in July 2010, an Mi-8 helicopter crashed there. In October 2011, the crashed helicopter was taken down in parts (but in vain - it could have been a good shelter). Now all that remains is the blade frozen in the ice.

Helicopter on the Lenz rocks (2010 photo)

You can put up a tent on the helipad, or a little lower in the trough. It should be kept in mind that there can be very strong winds on the Lenz cliffs. Further, the ascent to the Eastern peak goes between two rocky ridges, to the upper cliffs of Lenz (5200), to the so-called “gate”.

Upper cliffs of Lenz. View from the helipad.

Above the Lenz rocks there is a climb to the summit dome, which is not visible from below - and there is still at least 400 meters of elevation gain.

Elbrus from above. Ascent path from the north

You can also traverse from the middle cliffs of Lenz to Elbrus saddle(about 5300). This path is longer, but from the saddle you can go to both the Eastern peak of Elbrus and the Western one. The traverse from the Lenz rocks to the Elbrus saddle passes through an area replete with cracks - movement in ligaments!

The path to the Elbrus saddle from the Lenz rocks

Actually, the saddle of Elbrus is a rocky lintel. There is a hut on the saddle - This is the Red Fox 5300 rescue shelter., intended only for emergency situations . It means that you shouldn't plan to spend the night there- the hut can only be used in case of emergency. Builders of “Red Fox 5300”, Russian Mountaineering Federation and Red company Fox appeals to all Elbrus climbers who will have to use the shelter:

- Carefully close both doors (external and internal), this will save you from being swept away by snow.

- Clean up and take away trash after yourself.

- Be careful when using stoves and burners: poisoning from combustion products is possible.

Directly from the jumper, the climb to the Eastern peak of Elbrus begins, the trail to the Western peak begins to the south.

Climbing

6 day. 05/02/2013. Climbing Elbrus East from the north through the saddle.We leave around 2:30. It's clear, the thermometer is -7C, the wind is not strong. About half an hour later the Moon came out (almost full), you can walk without a flashlight. We are not walking fast, but almost without rest - it’s still cold to stand. We sat a little above the first ice takeoff and on the rocks. It began to get light on the approach to the Lenz rocks.

In a trough near the lower cliffs of Lenz we stopped to rest and take photographs. We untie ourselves, put the rope in our backpack - higher up on the classic route to the Eastern Peak it is not needed, there are no cracks.

Dawn on the Lenz rocks

Twenty minutes later the sun is already hot. We climb along the Lenz rocks; in some places, markers from last year have been preserved.

We climb along the Lenz rocks

Having reached the “helipad”, we began to decide which option to go to the top - and ultimately followed the footsteps of the group ahead to the col. The climb is very smooth and very long. You walk, gradually skirting the Eastern peak of Elbrus, but the saddle is still not visible. Finally, a rocky lintel appeared ahead - this is the Elbrus Saddle. A little higher on the left, on the slope of the Eastern peak, there is a hut, this is a new shelter.

From the saddle there is still a climb to the Eastern peak. Mostly on snow, and only in the upper part there is scree. On the opposite side you can see the ascent path to the Western Peak - a real “folk trail”. Even on May 2 there is a line there, it’s scary to think what’s going on there in the summer in good weather.

Trail to the Western peak of Elbrus

Finally the top. The eastern peak of Elbrus, in contrast to the pronounced Western peak, is a wide dome. More precisely, it is not a clearly defined crater. One elevation immediately upon ascending from the saddle, but the “official” summit with memorial signs is on the opposite side. In the north there is a rock, there is a version that the most high point is located right there.

Rock on the Eastern peak of Elbrus

Traditional photos at the top.

Memorial sign on the Eastern peak of Elbrus

On the Eastern peak of Elbrus

On the Eastern peak of Elbrus

And down. We descend along the familiar road through the saddle. We walk slowly - we feel tired. On the Lenz rocks we were treated to tea by a group standing there planning to cross the saddle to Azau.

There was movement at the Northern Shelter - several groups approached from below. But it was quiet: 8 people went to Elbrus that day - everyone who was in the camp that day, and 4 more people spent the night on the Lenz rocks.

7 day. 05/03/2013. Down to the Sirkh clearing.

In the morning we slowly pack up and go down the already familiar road. Over the past few days the snow has melted a lot. Numerous groups come to the meeting all day - we went on time. The earliest arrived at 9 am - yesterday they “didn’t make it” and spent the night in Moonlight Glade.

Elbrus - highest peak Caucasus, Russia and Europe. A two-headed stratovolcano, the peaks of which: Western (5642 m) and Eastern (5621 m) are separated by a saddle (5200 m) and are approximately 3 km apart. The first successful ascent of Elbrus was made in 1829 during an expedition led by General G.A. Emmanuel.

One of the local guides K. Khashirov (he was a Karachay or a Kabardian is still debated) first set foot on the Eastern peak on July 10, 1829. Since then, thousands of people have visited both peaks of Elbrus, but the relative ease of climbing (climbing category 2A) is very deceptive . Elbrus does not forgive mistakes and does not tolerate self-confidence. This is a difficult and serious mountain. It is vitally important to remember this if you are planning to go to Elbrus...

The most popular climbing routes to both peaks of Elbrus are laid from the south, have a developed lifting infrastructure (funiculars, snowcats), as well as hotels and shelters of varying degrees of comfort. We will go the other way: from the north, as the members of the first Russian expedition of 1829 went. Without special infrastructure, relying on our own strength and experienced organizers of ascents from the north - the mountain club "Lakkolit"

UPD: The bird in the top photo is not Photoshop, it was included in the frame by accident :-)

The journey from Kislovodsk to Base Camp (2500 m) takes about 3 hours in a UAZ.

River Kyzylkol.

Emmanuel Glade, base camp 2500 m.

Mineral springs (narzans) of Djily-Su. Popular place for therapeutic relaxation.

In the background is the Sultan waterfall 40 m.

On the slopes there are such “pencils”.

And these ones resemble the famous Moai from Easter Island, if in profile...

Our first exit to the upper (assault) camp. Dropping things off and acclimatizing.

"German airfield".

"Moonlight Glade" and the first glacier encountered.

Shelter "Lakkolit", assault camp 3800 m.

Not always on Elbrus good weather. Still life.

During boring acclimatization, you can entertain yourself by dragging stones...

Or you can just sit “on the rubble.” On the left is the kitchen, on the right is the dining room.

Lenz rocks and peak. The two lines below on the path are people.

Presidential Suite. No others.

Dawn.

Acclimatization hike to the Lenz rocks.

It would seem that there is nothing complicated: you go and go, but... there are nuances.

"And the mountains are getting higher, and the mountains are getting steeper,

And the mountains go under the very clouds"

Ahead, Roman Kanaev is an excellent guide, he helped me a lot on the climb.

Lenz Rocks (lower - 4600 m) You can relax.

Game with clouds "through the windows": one way...

And to another.

It's getting light.

Climbing. Somewhere in the middle of the Lenz cliffs, approximately 4800 m.

Are you weak?

They say the real peak is the top point of this rock.

The official peak is Elbrus-Eastern 5621 m.

"Victory Banner".

"You won't find it below, no matter how hard you reach,

Throughout my entire happy life...

A tenth of such beauties and wonders" V. Vysotsky

The way home.

Military equipment on vacation.

The fate of the lamb in the Caucasus is very predictable.

In Russia the roads are generally good, and especially in the mountains :-)

Well, sometimes it happens that you come across some kind of carnation...

Goodbye Elbrus and thank you!

UPD:

Being already a person who knows what Elbrus looks like, I bought a bottle of Narzan and something seemed suspicious to me

Mountain systems are perhaps one of the most monumental and impressive creations of nature. When you look at the snow-covered peaks, lined up one after another for hundreds of kilometers, you can’t help but wonder: what kind of immense force created them?

Mountains always seem to people like something immutable, ancient, like eternity itself. But the data of modern geology perfectly demonstrate how changeable the relief is. Mountains can be located where the sea once splashed. And who knows which point on Earth will be the highest in a million years, and what will happen to the majestic Everest...

Mechanisms of mountain range formation

To understand how mountains are formed, you need to have a good understanding of what the lithosphere is. This term refers to the outer shell of the Earth, which has a very heterogeneous structure. On it you can find peaks thousands of meters high, the deepest canyons, and vast plains.

The earth's crust is formed by giant rocks that are in continuous motion and from time to time collide with their edges. This leads to the fact that certain parts of them crack, rise and change the structure in every possible way. As a result, mountains are formed. Of course, the change in the position of the plates occurs very slowly - only a few centimeters per year. However, it was precisely due to these gradual shifts that dozens of mountain systems were formed on Earth over millions of years.

The land has both sedentary areas (mostly large plains are formed in their place, such as the Caspian plain), and rather “restless” areas. Basically, ancient seas were once located on their territory. At a certain moment, a period of intense pressure and pressure of approaching magma began. As a result sea bottom, with all its diversity of sedimentary rocks, rose to the surface. So, for example, there arose

As soon as the sea finally “retreats”, the rock mass that appears on the surface begins to be actively affected by precipitation, winds and temperature changes. It is thanks to them that each mountain system has its own special, unique relief.

How are tectonic mountains formed?

Scientists believe the movement of tectonic plates is the most accurate explanation of how folded and block mountains. When the platforms shift, the earth's crust in certain areas can be compressed, and sometimes even break, rising from one edge. In the first case, they are formed (some of their areas can be found in the Himalayas); another mechanism describes the emergence of blocky ones (for example, Altai).

Some systems feature massive, steep, but not too separated slopes. This is a characteristic feature of block mountains.

How are volcanic mountains formed?

The process by which volcanic peaks form is quite different from how fold mountains form. The name speaks quite clearly about their origin. Volcanic mountains arise in the place where magma - molten rock - breaks through to the surface. It can come out through one of the cracks in the earth's crust and accumulate around it.

In some parts of the planet, entire ridges of this type can be observed - the result of the eruption of several nearby volcanoes. Regarding how mountains are formed, there is also the following assumption: molten rocks, not finding a way out, simply press on the surface of the earth’s crust from the inside, as a result of which huge “bulges” appear on it.

A separate case is underwater volcanoes located at the bottom of the oceans. The magma that comes out of them can harden, forming entire islands. Countries such as Japan and Indonesia are located precisely on land areas of volcanic origin.

Young and ancient mountains

The age of the mountain system is clearly indicated by its relief. The sharper and higher the peaks, the later it was formed. Mountains that were formed no more than 60 million years ago are considered young. This group includes, for example, the Alps and the Himalayas. Research has shown that they arose about 10 million years ago. And although there was still a huge amount of time left before the appearance of man, in comparison with the age of the planet this is a very short period of time. The Caucasus, Pamir and Carpathians are also considered young.

An example of ancient mountains is the Ural ridge (its age is more than 4 billion years). This group also includes the North and South American Cordilleras and the Andes. According to some reports, the most ancient mountains on the planet are located in Canada.

Modern mountain formation

In the 20th century, geologists came to an unequivocal conclusion: enormous forces lie in the bowels of the Earth, and the formation of its relief never stops. Young mountains “grow” all the time, increasing in height by about 8 cm per year, ancient ones are constantly destroyed by wind and water, slowly but surely turning into plains.

A striking example of the fact that the process of changing the natural landscape never stops is the constantly occurring earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Another factor influencing the process of how mountains are formed is the movement of rivers. When a certain area of land rises, their channels become deeper and cut into the rocks more strongly, sometimes creating entire gorges. Traces of rivers can be found on the slopes of peaks, along with the remains of valleys. It is worth noting that the same natural forces that once formed their relief are involved in the destruction of mountain ranges: temperatures, precipitation and winds, glaciers and underground springs.

Scientific versions

Modern versions of orogeny (the origin of mountains) are represented by several hypotheses. Scientists put forward the following probable reasons:

- subsidence of oceanic trenches;

- drift (sliding) of continents;

- subcrustal currents;

- swelling;

- reduction of the earth's crust.

One version of how mountains are formed is associated with the action. Since the Earth is spherical, all particles of matter tend to be located symmetrically relative to the center. In addition, all rocks differ in mass, and the lighter ones over time are “pushed out” to the surface by the heavier ones. Together, these reasons lead to the appearance of irregularities in the earth's crust.

Modern science is trying to determine the underlying mechanism of tectonic change based on which mountains were formed as a result of which process. There are still many questions associated with orogenesis that still remain unanswered.

Read Climbing Elbrus part 1.

DAY 3 and 4 are described

General information about the route

Route thread

lane Irekchat (1b) - ice. Jikaukengoz (3300m) - level. Birjal - camp of the Ministry of Emergency Situations

Day 3

Route section: R. Irikchat - per. IrikChat (east) (1B) - Jikaugenkez glacier - Kynchyryrt glacier.

Elevation gain:509 m

LP on the site: Irik-Chat pass (1B height 3643, east - kurumnik, talus slope, west - frozen talus slope 60 o, ice field)

The duty personnel wake up at 5:00. Everyone else gets up at 6.00. Clear. The group is in combat condition. There are no symptoms of altitude sickness. We leave at 7.00 in the direction of the Irik-Chat pass. The pass leads from the river valley. Irik-Chat to the Jikaugenkez glacier. The ascent to it begins along the left bank of the river bed. Irikchat. The right bank of the river is quite steep and is also covered by the Irikchat glacier. You can go up to the pass by two paths, the glory and to the right of the rock polished by the glacier, this form of relief is called “ram’s forehead”.

The left path is scree, quite steep, and leads along the glacier. Therefore, we chose a safer path along the right path, which goes out onto the southern slope of the ridge of Mount Chatkara. The slope is a moraine, destroyed by modern talus gravitational processes. The trail is not marked with tours everywhere; in some places it was destroyed by mudflows and landslides. We gallop along the ridge, looking for tours and a path between the stones. We took the pass quickly at 9.35, having a snack before taking off.

The Irik-Chat pass is oriented from east to west. Elevation 3643m. KS 1B. The eastern takeoff is a scree slope, steep up to 40 degrees. The western one is an icy scree slope of about 60 degrees, about 3 m high, ending with an ice shelf under the takeoff of the pass. We go through the eastern takeoff with a traverse, while we go down the western takeoff in ropes and crampons, digging into the ground. At the top of the pass we met Poles who spent the night right there on the pass before the assault on Elbrus. They probably planned to climb along one of the most difficult paths - from the side of the lava flow.

Oleg said that the Caspian Sea should extend to the east of the pass, and the Black Sea to the west. Without hesitation, we ran to take a look at Chernoye, where it’s warm and you don’t need to wear down jackets and hats in the summer. But the leader stopped us, ordering us to put on crampons and systems and prepare to descend under the pass on its western side into the ice and cold. The pass offers views of the eastern peak of Elbrus and its northern valley. From the north - the top of Chatkara, from the south - Askerkolbashi-Tersak. On the shelf under the western takeoff of the pass, we split into two groups, tie up, arm ourselves with ice axes and begin the descent. The descent from the pass is an ice field with lenses of melted ice. The slope is steep, in some places up to 45 degrees. It’s scary to walk, the backpack tries to hang forward, there is a danger of flying upside down. It was very good that there was no wind. Below the slope flattens out.

Eastern slope of Elbrus

Next, our path goes along a frozen lake (another name is the Jikauchennez Snow Valley). Streams flow in places, but the surface is still icy. There are small cracks. We bypass the area of large cracks from the south. Walking with crampons is not easy; every step must be taken care of. At 11.20 we have a snack on the rocks near the river flowing from the Elbrus glacier. The stones are located in the section of the snowy valley of Jikauchennez and the Kynchyrsyrt Glacier. To the north we see an unnamed peak (3581.0m), beyond it stretches the Chungur-Chat-Chirak Glacier, where we were supposed to go according to the agreed trek plan.

Our route changed due to weather conditions. The meteorological report showed that the weather will begin to deteriorate from September 20. Therefore, the leader decided to slightly adjust the plan, moving the ascent day 2 days earlier from September 21 to September 19.

After a snack, we walk along the ice field, completely cut by many streams towards the Kynchyrsyrt glacier, along the northern foot of Elbrus. The rivers from the glaciers are turbulent, the channels are deep and wide - up to a meter. The water here is clean, transparent and terribly cold. The boys swam in one of the streams, and the girls decided to sunbathe a little.

The upper boundary of the Kynchyrsyrt glacier has many cracks; we go around this area from the north. But even here there are small cracks that are visible to the naked eye. Therefore, we pass them calmly, ice axes at the ready. We're going tight. The maximum visible width of the cracks that we overcome reaches 30-40cm, the bottom is not visible. We cross a wide river from a glacier. We don't make railings. We throw the backpacks over to the other side. We step over ourselves, belaying ourselves in front and behind. The final point of the route of this day ends on a stone tongue between the Kynchyrsyrt glacier and the Mikelysran glacier (another name is Mikel Chiran).

Taking into account the passage of the pass and the glacier, the day turned out to be very intense for physical activity. Everyone is tired. Spending the night in the rocks, on a flat sandy area, like a gift from fate. The place is beautiful and a little magical. We got up for the night at 18:30. It becomes a little uneasy when, in the silence of the night, one of your friends hurries in search of a toilet, and each of his steps vibrates and echoes beneath you in the belly of the rock, making it seem as if the tent is about to fall down. The altitude is 3757 m. We measure morning and evening pulses throughout the route. Everyone's pulse is normal. There are no symptoms of altitude sickness.

North-eastern slope of Elbrus. The girls will be overwhelmed with emotions.))

Camp. Day 3

Day 4.

Route section:glacier Mikelshran (Mikel Chiran) - Base of the Ministry of Emergency Situations (north) assault camp.

Elevation gain: 128 m

Elevation gain, taking into account the training climb to the N. rocks of Lenz: 745m

Height drop taking into account the training exit to the N. rocks of Lenz: 745 m

LP in the area: north-eastern slope of Elbrus, Lenz rocks (2A, 4630 m, glaciated slope with lenses of thawed ice, firn in places)

The duty personnel wake up at 6:00. Everyone else gets up at 7.00. And again a gift of fate)) morning duty. Morning in the mountains is a light show arranged by nature. First, the edge of the dark, almost black sky is illuminated in red, yellow, the stars begin to disappear, and, in the end, only one remains - the morning one. But it also disappears, giving way to the sun, which paints the mountain tops pink and lilac.

Milk rivers of the Caucasus

For breakfast again, quick porridge and waffles with tea. Tasty. The weather is calm and clear. This is the day we are coming to base camp on the northern slope of Elbrus. We leave at 8.10 towards the Mikelsran glacier (Mikel-Chinar). We walk between the boulders of ancient madder along a large kurumnik with living stones.

After 200 meters we reach the Mikelsran glacier (Mikel Chiran), on the surface of the firn glacier there is highly compressed snow, in places with lenses of ice. We pass the glacier without hindrance. The western border of the glacier abuts the moraine. In search of a place to spend the night, we walk along its border to south direction, and we find a suitable site in close proximity to the path leading to the eastern peak of Elbrus, which is very beneficial for us.

At 9.20 we set up camp on an ancient lava flow, which was greatly transformed after glaciation, as well as frost weathering, which gave a good start for the occurrence of new gravitational processes in the form of screes and landslides. We stopped on a flat area fenced with a windproof wall. Elevation 3885m. We collect our backpacks for the training/acclimatization climb to the lower cliffs of Lenz. To get as close as possible to the conditions of climbing to the top, we take all the necessary things. We put warm clothes, an ice ax, a system with carabiners, and water in the backpack.

Assault camp. Altitude 3900 m

Below our camp are the houses of the northern shelter. From there, an hour before our acclimatization trip to the lower cliffs of Lenz, a group left, accompanied by two instructors. Spurred on by the leader’s grumbling that at this rate we would never reach the top, we caught up with this group and overtook them almost halfway to the rocks.

The beginning of the trail to the rocks is a fairly steep climb up to 42 degrees. The slope is glaciated with lenses of thawed ice and firn in places. We're wearing crampons. We don't make connections. Near our camp there were several tents with tourists, from whom we asked about the need to walk in bundles, cracks and other dangers. This season the cracks have been closed, the path has been found. Therefore, we go in crampons and with ice axes.

The only stop before the N. Lenz rocks is at the “Divan” stone. Here you can sit, comfortably throw your backpack, take a breath and drink tea.

The Lenz Rocks are rocks made of lava and protruding from the glacier covering the slope of Elbrus. Rocks Lenz represent some rock ridges stretching parallel to approximately the height 5200. Emilius Khristianovich Lenz - Russian physicist from the Baltic Germans. On July 10, 1829, as part of the expedition of General G. Emmanuel, he climbed the northern slope of Elbrus above the upper limit of the rocks to a saddle height of 5300 m, so the rocks were later named after him.

Departure to the lower cliffs of Lenz at 12.20. After 2 hours we were at the top. Elevation 4630m. The descent to camp took about an hour. Endurance test passed. I can breathe normally. High physical activity causes the heart to beat quickly, which is why you have to make short stops to restore your breathing and pulse. Time spent on ascent and descent - 3 hours 40 minutes.

In the evening we admired the sunset and discussed the training ascent and descent. We made plans for tomorrow's day off. My proposal to ride on mats down the mountain was rejected, because it is dangerous, you can hurt yourself, and besides, there is no need to spoil public equipment, but it would be fun... Various variations of the implementation of rides were also not successful.

The clouds in the valley put on a show for us. Either they turned into a giant bird with outstretched wings, or into a clawed paw/wing. The sun's rays also tried their best: they refracted at unimaginable angles, drawing mysterious geometric patterns. The evening was cool and quiet. The group's health is excellent. The pulse is normal, there are no symptoms of miner, with the exception of a slight headache in some.

In the evening, while admiring Elbrus, we noticed three climbers descending the path from the mountain. We rooted for this trio with all our hearts. Poor fellows, they could barely walk. They fell, got up and walked again, trying to slide down on their fifth point. We decided that the guys had at least conquered both peaks.

The next day we met with them. It turned out that everything was much more banal, they walked slowly, preparing breakfast, lunch and dinner along the way) and only descended from the mountain at about 20.00.