slide 1

slide 2

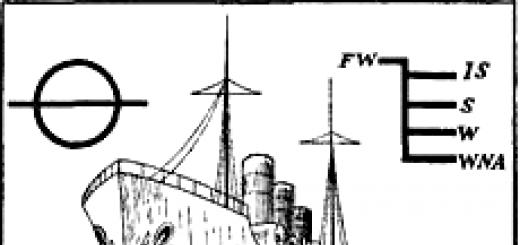

Plan of the Winter Palace. 1. Jordan Gallery /ground floor/ 2. Main (Jordanian) staircase 3. Field Marshal's Hall 4. Petrovsky (Small Throne) Hall 5. St. George's (Large Throne) Hall 6. Military Gallery of 1812 7. Armorial Hall 8. Big Church 9 Alexander Hall 10. Halls of military paintings 11. Large living room 12. White Hall 13. October staircase 14. Golden living room 15. Crimson study 16. Boudoir 17. Study room 18. Bedroom 19. Rotunda 20. Library of Nicholas II 21. Malaya ( White) dining room 22. Malachite living room 23. Large Arap dining room 24. Concert hall 25. Portrait gallery of the Romanovs' house 26. Big (Nikolaev) hall 27. Anteroom

Plan of the Winter Palace. 1. Jordan Gallery /ground floor/ 2. Main (Jordanian) staircase 3. Field Marshal's Hall 4. Petrovsky (Small Throne) Hall 5. St. George's (Large Throne) Hall 6. Military Gallery of 1812 7. Armorial Hall 8. Big Church 9 Alexander Hall 10. Halls of military paintings 11. Large living room 12. White Hall 13. October staircase 14. Golden living room 15. Crimson study 16. Boudoir 17. Study room 18. Bedroom 19. Rotunda 20. Library of Nicholas II 21. Malaya ( White) dining room 22. Malachite living room 23. Large Arap dining room 24. Concert hall 25. Portrait gallery of the Romanovs' house 26. Big (Nikolaev) hall 27. Anteroom

slide 3

History pages. The Winter Palace is a grand building, which is the oldest building on Palace Square built in the Baroque style. Like any building in St. Petersburg, the Winter Palace is shrouded in stories and myths. Officially, the construction of the Winter Palace, designed by B.F. Rastrelli, began in 1754 and ended in 1762, but the history of its creation dates back much earlier. On the site now occupied by the palace in 1712 under Peter the Great, it was forbidden to give plots of land to persons who did not belong to the naval ranks. Peter the Great, wishing to build a palace for himself on this site, received permission to build Peter Alekseev as a shipbuilder and built a residential "small house of Dutch architecture" there. In front of its side facade, in 1718, a canal was dug, named after the palace as the Winter Canal. In 1711, specifically for the wedding of Peter I and Catherine, the architect Matornovi, by order of the tsar, began to rebuild the wooden palace into a stone one. But in the process of work, the architect G. Matornovi was removed from business and the construction was headed by Trezzini. In 1720, Peter I and his entire family moved from their summer residence to their winter residence. In 1723, the Senate was transferred to the Winter Palace.

History pages. The Winter Palace is a grand building, which is the oldest building on Palace Square built in the Baroque style. Like any building in St. Petersburg, the Winter Palace is shrouded in stories and myths. Officially, the construction of the Winter Palace, designed by B.F. Rastrelli, began in 1754 and ended in 1762, but the history of its creation dates back much earlier. On the site now occupied by the palace in 1712 under Peter the Great, it was forbidden to give plots of land to persons who did not belong to the naval ranks. Peter the Great, wishing to build a palace for himself on this site, received permission to build Peter Alekseev as a shipbuilder and built a residential "small house of Dutch architecture" there. In front of its side facade, in 1718, a canal was dug, named after the palace as the Winter Canal. In 1711, specifically for the wedding of Peter I and Catherine, the architect Matornovi, by order of the tsar, began to rebuild the wooden palace into a stone one. But in the process of work, the architect G. Matornovi was removed from business and the construction was headed by Trezzini. In 1720, Peter I and his entire family moved from their summer residence to their winter residence. In 1723, the Senate was transferred to the Winter Palace.

slide 4

Winter Palace in the 18th century. (Portrait of Anna Ivanovna) When the reign of Anna Ivanovna came, Count Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli, a brilliant architect of that time, offered her his project for the reconstruction of the Winter Palace. According to his project, it was required to purchase houses that stood at that time on the site occupied by the current palace and belonged to Count Apraksin, the Naval Academy, Raguzinsky and Chernyshev. Anna Ioanovna approved the project, the houses were bought up, and construction began. In 1735, the construction of the palace was completed, and Anna Ioannovna moved into it to live. The palace looked a little different than it currently exists. In the opinion of Elizabeth Petrovna, who ascended the throne, he did not meet the requirements of the official residence of the Russian Empress. By her order in 1754, Count Rastrelli was to draw up new project Winter Palace. Rastrelli, in accordance with the wishes of Elizabeth Petrovna, tried to create a palace that the Russian capital could be proud of. The palace was given the appearance that has been preserved to this day. 859,555 rubles were allocated for the work, which at that time was an extremely modest amount for such a project. And, nevertheless, the author and his assistants managed to emphasize the richness and diversity of the decoration of the Winter Palace. About four thousand people worked on its construction. It was possible to gather the best masters from all over the country. Now the Palace Square and the Alexander Garden were covered with huts in which the workers lived. The palace turned out as planned, not like the others.

Winter Palace in the 18th century. (Portrait of Anna Ivanovna) When the reign of Anna Ivanovna came, Count Bartolomeo Francesco Rastrelli, a brilliant architect of that time, offered her his project for the reconstruction of the Winter Palace. According to his project, it was required to purchase houses that stood at that time on the site occupied by the current palace and belonged to Count Apraksin, the Naval Academy, Raguzinsky and Chernyshev. Anna Ioanovna approved the project, the houses were bought up, and construction began. In 1735, the construction of the palace was completed, and Anna Ioannovna moved into it to live. The palace looked a little different than it currently exists. In the opinion of Elizabeth Petrovna, who ascended the throne, he did not meet the requirements of the official residence of the Russian Empress. By her order in 1754, Count Rastrelli was to draw up new project Winter Palace. Rastrelli, in accordance with the wishes of Elizabeth Petrovna, tried to create a palace that the Russian capital could be proud of. The palace was given the appearance that has been preserved to this day. 859,555 rubles were allocated for the work, which at that time was an extremely modest amount for such a project. And, nevertheless, the author and his assistants managed to emphasize the richness and diversity of the decoration of the Winter Palace. About four thousand people worked on its construction. It was possible to gather the best masters from all over the country. Now the Palace Square and the Alexander Garden were covered with huts in which the workers lived. The palace turned out as planned, not like the others.

slide 5

slide 6

Slide 7

Winter Palace in the 18th century. Its facades are decorated with the variety inherent in Rastrelli, each of which the architect gave a peculiar interpretation. Strongly protruding wings of the western facade facing the Admiralty form the main courtyard. The architects gave the same architectural solution to the eastern end of the palace, hidden by the building of the Small Hermitage. The northern façade, facing the Neva, is richly decorated with two-tiered white columns, creating a spectacular play of chiaroscuro. The main one - the southern facade, oriented to the Palace Square, is cut through by three entrance arches. The light green color of the walls contrasts favorably with the whiteness of the columns. The decorativeness of the building is enhanced by the whimsical curves of the complex cornices and the diverse window frames. Their composition includes the heads of cupids, lion masks, whimsical curls, characteristic of the Baroque style. 176 sculptural figures on the roof, alternating with vases, enliven the silhouette of the palace, emphasizing the dynamics of its forms. The building is striking in its scale. Inside it there are 1050 front and residential halls with an area of 46 thousand square meters, 1945 windows, 1786 doors, 117 stairs, 329 chimneys. Total length the main cornice that borders the building is almost two kilometers long. The whole system of external decorations was designed to emphasize the unprecedented height of the building at that time. This impression was reinforced by the columns arranged in two tiers. But Elizabeth did not have to live in this magnificent creation of architecture.

Winter Palace in the 18th century. Its facades are decorated with the variety inherent in Rastrelli, each of which the architect gave a peculiar interpretation. Strongly protruding wings of the western facade facing the Admiralty form the main courtyard. The architects gave the same architectural solution to the eastern end of the palace, hidden by the building of the Small Hermitage. The northern façade, facing the Neva, is richly decorated with two-tiered white columns, creating a spectacular play of chiaroscuro. The main one - the southern facade, oriented to the Palace Square, is cut through by three entrance arches. The light green color of the walls contrasts favorably with the whiteness of the columns. The decorativeness of the building is enhanced by the whimsical curves of the complex cornices and the diverse window frames. Their composition includes the heads of cupids, lion masks, whimsical curls, characteristic of the Baroque style. 176 sculptural figures on the roof, alternating with vases, enliven the silhouette of the palace, emphasizing the dynamics of its forms. The building is striking in its scale. Inside it there are 1050 front and residential halls with an area of 46 thousand square meters, 1945 windows, 1786 doors, 117 stairs, 329 chimneys. Total length the main cornice that borders the building is almost two kilometers long. The whole system of external decorations was designed to emphasize the unprecedented height of the building at that time. This impression was reinforced by the columns arranged in two tiers. But Elizabeth did not have to live in this magnificent creation of architecture.

Slide 8

Winter Palace in the 18th century. Portrait of Peter III. In 1762, the work was completed, and on April 6 of the same year, Emperor Peter III moved to live in the Winter Palace. He watches with pleasure from the window of the palace, as the city dwellers take away the rubbish left after construction work, thereby clearing the area in front of the palace, which seemed incredible. This simple decision was prompted to Peter III by General-Police Chief N.A. Korf. But Peter III did not have long to enjoy the beauty of the Winter Palace. In 1763, Catherine II was already entering it, having returned from Moscow after the coronation. By her arrival, the decorations of all the interior of the palace with all the decorations available in it were completed. By the end of the XVIII century. in the palace there were up to 1500 rooms, among which, according to the special luxurious decoration and the works of art collected here, it is necessary to single out such halls as: the Romanov gallery containing a collection of portraits of the Sovereigns of the Romanov dynasty, starting with Mikhail Fedorovich. St. George's Hall, in which there is a golden throne, with a large imperial coat of arms embroidered in gold on a red velvet background. The hall is decorated with marble columns and six magnificent chandeliers, and many other halls. A winter garden was also created in the palace, with large trees - tropical and northern.

Winter Palace in the 18th century. Portrait of Peter III. In 1762, the work was completed, and on April 6 of the same year, Emperor Peter III moved to live in the Winter Palace. He watches with pleasure from the window of the palace, as the city dwellers take away the rubbish left after construction work, thereby clearing the area in front of the palace, which seemed incredible. This simple decision was prompted to Peter III by General-Police Chief N.A. Korf. But Peter III did not have long to enjoy the beauty of the Winter Palace. In 1763, Catherine II was already entering it, having returned from Moscow after the coronation. By her arrival, the decorations of all the interior of the palace with all the decorations available in it were completed. By the end of the XVIII century. in the palace there were up to 1500 rooms, among which, according to the special luxurious decoration and the works of art collected here, it is necessary to single out such halls as: the Romanov gallery containing a collection of portraits of the Sovereigns of the Romanov dynasty, starting with Mikhail Fedorovich. St. George's Hall, in which there is a golden throne, with a large imperial coat of arms embroidered in gold on a red velvet background. The hall is decorated with marble columns and six magnificent chandeliers, and many other halls. A winter garden was also created in the palace, with large trees - tropical and northern.

Slide 9

slide 10

slide 11

Winter Palace in the 19th century. The Winter Palace acquired its completion during the reign of Emperor Nicholas I (1825-1855). The grandson of the great Catherine II and the younger brother of Tsar Alexander I, Nicholas ascended the throne, brutally suppressing the uprising on December 14, 1825 - the first organized uprising against tsarism. All further policy of his reign was aimed at strengthening the power and authority of autocratic power. Having become the owner of the Winter Palace, Nicholas, in order to raise the prestige of the main imperial residence, gives orders to expand the front part of the palace. First of all, he implements the idea, conceived by Alexander I, of creating a portrait gallery in the palace in memory of the victory over Napoleon. Back in 1819, the painter George Doe was invited from England, who was instructed to paint portraits of all Russian generals who participated in the campaigns of 1812-1815. Dow, who was assisted by the Russian painters A.V. Polyakov and V.A. Golike, painted 332 portraits of those who were still alive, and those who were no longer alive and whom he painted from the preserved lifetime images. In 1826, the famous St. Petersburg architect K. Rossi (1775/77-1849) built a 55 m long gallery in the Winter Palace, where painted portraits were placed. That's how it was created unique monument Military Glory of Russia - Military Gallery of 1812.

Winter Palace in the 19th century. The Winter Palace acquired its completion during the reign of Emperor Nicholas I (1825-1855). The grandson of the great Catherine II and the younger brother of Tsar Alexander I, Nicholas ascended the throne, brutally suppressing the uprising on December 14, 1825 - the first organized uprising against tsarism. All further policy of his reign was aimed at strengthening the power and authority of autocratic power. Having become the owner of the Winter Palace, Nicholas, in order to raise the prestige of the main imperial residence, gives orders to expand the front part of the palace. First of all, he implements the idea, conceived by Alexander I, of creating a portrait gallery in the palace in memory of the victory over Napoleon. Back in 1819, the painter George Doe was invited from England, who was instructed to paint portraits of all Russian generals who participated in the campaigns of 1812-1815. Dow, who was assisted by the Russian painters A.V. Polyakov and V.A. Golike, painted 332 portraits of those who were still alive, and those who were no longer alive and whom he painted from the preserved lifetime images. In 1826, the famous St. Petersburg architect K. Rossi (1775/77-1849) built a 55 m long gallery in the Winter Palace, where painted portraits were placed. That's how it was created unique monument Military Glory of Russia - Military Gallery of 1812.

slide 12

Romanov Gallery The gallery displays portraits of representatives of the Romanov dynasty - from the founder of the Russian Empire, Peter the Great, to the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II. The gallery, then called Pompeii, was created after the fire of 1837 by V.P. Stasov, who placed next to it, above the Embassy entrance overlooking the courtyard, the Winter Garden with a glazed ceiling. In 1886, it was decided to place paintings in the gallery, in connection with which, according to the project of the palace architect N.A. Gornostaev, its decoration was changed. IN exhibition hall arranged after the Great Patriotic War on the site of the garden, there is an exposition "Russian culture of the 17th century."

Romanov Gallery The gallery displays portraits of representatives of the Romanov dynasty - from the founder of the Russian Empire, Peter the Great, to the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II. The gallery, then called Pompeii, was created after the fire of 1837 by V.P. Stasov, who placed next to it, above the Embassy entrance overlooking the courtyard, the Winter Garden with a glazed ceiling. In 1886, it was decided to place paintings in the gallery, in connection with which, according to the project of the palace architect N.A. Gornostaev, its decoration was changed. IN exhibition hall arranged after the Great Patriotic War on the site of the garden, there is an exposition "Russian culture of the 17th century."

slide 13

George Hall. Georgievsky (Large Throne) Hall, for which a special building was built, from the side Grand Palace, created in 1787-1795 under Catherine II according to the project of Giacomo Quarenghi (1744-1817). The new throne room was designed in strict classical forms. The huge double-height room made a stunning impression. But Quarenghi's masterpiece was destroyed in a fire in 1837. Emperor Nicholas I ordered "to try to make the St. George Hall ... all of white marble." White Carrara marble, which gave extraordinary solemnity to the Throne Hall, was delivered from Italy. The ceiling was decorated with gilded ornaments, the pattern of which was repeated in the parquet pattern of 16 types of colored wood. Above the throne place is a marble bas-relief "George the Victorious slaying the dragon with a spear". The St. George Hall was completed later than the other rooms of the palace due to the laboriousness of the marble cladding, and consecrated in 1841. The entire official history of the Russian royal house is associated with this hall. The majestic and solemn decoration of the hall corresponds to its purpose: official ceremonies and receptions were held here.

George Hall. Georgievsky (Large Throne) Hall, for which a special building was built, from the side Grand Palace, created in 1787-1795 under Catherine II according to the project of Giacomo Quarenghi (1744-1817). The new throne room was designed in strict classical forms. The huge double-height room made a stunning impression. But Quarenghi's masterpiece was destroyed in a fire in 1837. Emperor Nicholas I ordered "to try to make the St. George Hall ... all of white marble." White Carrara marble, which gave extraordinary solemnity to the Throne Hall, was delivered from Italy. The ceiling was decorated with gilded ornaments, the pattern of which was repeated in the parquet pattern of 16 types of colored wood. Above the throne place is a marble bas-relief "George the Victorious slaying the dragon with a spear". The St. George Hall was completed later than the other rooms of the palace due to the laboriousness of the marble cladding, and consecrated in 1841. The entire official history of the Russian royal house is associated with this hall. The majestic and solemn decoration of the hall corresponds to its purpose: official ceremonies and receptions were held here.

slide 14

Military gallery in 1812. The military gallery of 1812 - the most famous of the memorial premises of the palace - was built according to the project of the outstanding architect of Russian classicism K.I. Rossi (1775/77-1849) and solemnly opened on December 25, 1826, on the anniversary of the expulsion of Napoleon's army from Russia. 332 portraits of the generals of the Russian army, participants in the war of 1812 and the foreign campaign of 1813-1814 were placed here. Places were left in the Gallery for 13 portraits of the dead, whose images could not be found. The portraits were commissioned by Alexander I to the artist George Doe. The meeting of the Russian emperor and the fashionable English portrait painter took place in the German city of Aachen, where in the fall of 1818 the first congress of the Holy Union of the countries - the winners of the Napoleonic army took place. At the back of the hall, on the end wall, there is a ceremonial portrait of Emperor Alexander I (made by Franz Kruger). Nearby are ceremonial portraits, monarchs allied states- Prussia and Austria. Portraits of Field Marshal M.I. Kutuzov and M.B. Barclay de Tolly are on the sides of the door leading to the St. George (Large Throne) Hall. During the fire of 1837, all the portraits were saved and returned to their places in the hall restored by V.P. Stasov.

Military gallery in 1812. The military gallery of 1812 - the most famous of the memorial premises of the palace - was built according to the project of the outstanding architect of Russian classicism K.I. Rossi (1775/77-1849) and solemnly opened on December 25, 1826, on the anniversary of the expulsion of Napoleon's army from Russia. 332 portraits of the generals of the Russian army, participants in the war of 1812 and the foreign campaign of 1813-1814 were placed here. Places were left in the Gallery for 13 portraits of the dead, whose images could not be found. The portraits were commissioned by Alexander I to the artist George Doe. The meeting of the Russian emperor and the fashionable English portrait painter took place in the German city of Aachen, where in the fall of 1818 the first congress of the Holy Union of the countries - the winners of the Napoleonic army took place. At the back of the hall, on the end wall, there is a ceremonial portrait of Emperor Alexander I (made by Franz Kruger). Nearby are ceremonial portraits, monarchs allied states- Prussia and Austria. Portraits of Field Marshal M.I. Kutuzov and M.B. Barclay de Tolly are on the sides of the door leading to the St. George (Large Throne) Hall. During the fire of 1837, all the portraits were saved and returned to their places in the hall restored by V.P. Stasov.

slide 15

Fire in the Winter Palace in 1837. In 1828, O.R. Montferrand (1786-1858), a French architect invited to Russia by Alexander I in 1816, was involved in the work in the Winter Palace. While working on the construction of St. Isaac's Cathedral, which was destined to become one of the grandest buildings of the mid-19th century, Montferrand simultaneously created new apartments in the royal residence. In 1833-1834, next to the Main Palace Staircase, he built two halls that completed the formation of the main suite of state rooms of the Winter Palace - Field Marshal's and Petrovsky, dedicated to the memory of Peter the Great. Three years later, everything created by Montferrand and his predecessors in the Winter Palace perished in the fire of an unprecedented fire in December 1837. Fires in those days happened in St. Petersburg often, mainly due to stove heating, which was also in royal palace. On the first floor, under the Field Marshal and Petrovsky halls, there was a palace pharmacy, in which the stove was heated around the clock. On the evening of December 17, 1837, wisps of smoke began to seep out of the air vent in the Field Marshal's Hall. The alarmed staff on duty called the fire brigade. After examining the air vent, the attic and basement, the firefighters found smoky matting and abundantly filled everything with water from the brinesboys. However, the cause of the fire, which after a few minutes broke out from behind the collapsed wooden partition of the hall, was different ...

Fire in the Winter Palace in 1837. In 1828, O.R. Montferrand (1786-1858), a French architect invited to Russia by Alexander I in 1816, was involved in the work in the Winter Palace. While working on the construction of St. Isaac's Cathedral, which was destined to become one of the grandest buildings of the mid-19th century, Montferrand simultaneously created new apartments in the royal residence. In 1833-1834, next to the Main Palace Staircase, he built two halls that completed the formation of the main suite of state rooms of the Winter Palace - Field Marshal's and Petrovsky, dedicated to the memory of Peter the Great. Three years later, everything created by Montferrand and his predecessors in the Winter Palace perished in the fire of an unprecedented fire in December 1837. Fires in those days happened in St. Petersburg often, mainly due to stove heating, which was also in royal palace. On the first floor, under the Field Marshal and Petrovsky halls, there was a palace pharmacy, in which the stove was heated around the clock. On the evening of December 17, 1837, wisps of smoke began to seep out of the air vent in the Field Marshal's Hall. The alarmed staff on duty called the fire brigade. After examining the air vent, the attic and basement, the firefighters found smoky matting and abundantly filled everything with water from the brinesboys. However, the cause of the fire, which after a few minutes broke out from behind the collapsed wooden partition of the hall, was different ...

slide 16

Fire in the Winter Palace. A strong flame instantly engulfed the floors: the palace blazed from above. It was impossible to save him. The fire spread rapidly along the walls, along the carved wood of gilded ornaments, picturesque plafonds, and waxed parquets. Today it is obvious that the constructive mistake of the architect O.R.Montferrand, who placed the air vent in a narrow space fenced off by a partition, and the use of wood as the main building material led to tragic consequences. An eyewitness to the incident, A.P. Bashutsky, colorfully described the finale of a grandiose fire that raged for more than thirty hours. "They were solemnly sad last hours phoenix-buildings ... We saw through the broken windows how the fire walked victoriously in the desert expanse, illuminating wide passages, it either stabbed and collapsed marble columns, then boldly blackened precious gilding, then poured crystal and bronze chandeliers of artistic work into ugly piles, then he would tear off luxurious brocades and damasks from the walls ... ". When it became obvious to Nicholas I, who returned from the theater, that it was impossible to stop the raging elements, a decision was made: urgently take out everything that was possible from the palace. Furniture, dishes, crystal, chests with clothes, paintings, carpets, books, albums and other utensils - everything was piled right on the snow of Palace Square. To prevent the fire from spreading to the Hermitage, the passages between it and the palace were broken, and the walls behind which priceless artistic treasures were kept were kept under water pressure. The fire raged for three days. By the evening of December 19, only a giant charred skeleton remained from the Winter Palace.

Fire in the Winter Palace. A strong flame instantly engulfed the floors: the palace blazed from above. It was impossible to save him. The fire spread rapidly along the walls, along the carved wood of gilded ornaments, picturesque plafonds, and waxed parquets. Today it is obvious that the constructive mistake of the architect O.R.Montferrand, who placed the air vent in a narrow space fenced off by a partition, and the use of wood as the main building material led to tragic consequences. An eyewitness to the incident, A.P. Bashutsky, colorfully described the finale of a grandiose fire that raged for more than thirty hours. "They were solemnly sad last hours phoenix-buildings ... We saw through the broken windows how the fire walked victoriously in the desert expanse, illuminating wide passages, it either stabbed and collapsed marble columns, then boldly blackened precious gilding, then poured crystal and bronze chandeliers of artistic work into ugly piles, then he would tear off luxurious brocades and damasks from the walls ... ". When it became obvious to Nicholas I, who returned from the theater, that it was impossible to stop the raging elements, a decision was made: urgently take out everything that was possible from the palace. Furniture, dishes, crystal, chests with clothes, paintings, carpets, books, albums and other utensils - everything was piled right on the snow of Palace Square. To prevent the fire from spreading to the Hermitage, the passages between it and the palace were broken, and the walls behind which priceless artistic treasures were kept were kept under water pressure. The fire raged for three days. By the evening of December 19, only a giant charred skeleton remained from the Winter Palace.

slide 17

Field Marshal's Hall. The hall opens the Grand ceremonial suite of the Winter Palace. The interior was restored after a fire in 1837 by V.P. Stasov close to the original project of O. de Montferrand (1833 - 1834). The entrances to the hall, designed in a strict classical style, are punctuated by portals. The longitudinal walls are decorated with double pilasters, on which lies the entablature supporting the choirs. In the decor of gilded bronze chandeliers and grisaille paintings of the hall, motifs of military glory are used. Before the revolution, ceremonial portraits of Russian field marshals were placed in the niches of the hall, which explains its name. The hall presents monuments of Western European and Russian sculpture, as well as artistic porcelain from the Imperial Factory, created in the first half of the 19th century.

Field Marshal's Hall. The hall opens the Grand ceremonial suite of the Winter Palace. The interior was restored after a fire in 1837 by V.P. Stasov close to the original project of O. de Montferrand (1833 - 1834). The entrances to the hall, designed in a strict classical style, are punctuated by portals. The longitudinal walls are decorated with double pilasters, on which lies the entablature supporting the choirs. In the decor of gilded bronze chandeliers and grisaille paintings of the hall, motifs of military glory are used. Before the revolution, ceremonial portraits of Russian field marshals were placed in the niches of the hall, which explains its name. The hall presents monuments of Western European and Russian sculpture, as well as artistic porcelain from the Imperial Factory, created in the first half of the 19th century.

slide 18

Petrovsky Hall. The Petrovsky (Small Throne) Hall commemorates the founder of the Russian Empire, Peter I. The hall was created in 1833 according to the project of O.-R. Montferrand (1786-1858) and restored after a fire by V.P. Stasov almost unchanged. The decoration of the hall was the composition with the allegorical painting "Peter I with Minerva" by G. Amikoni. Elements of imperial paraphernalia - the monograms of Peter the Great, crowns, double-headed eagles - occupy a special place in the decoration of the hall. Picturesque images of the famous battles of the Northern War - the Poltava battle and the Battle of Lesnaya - allowed contemporaries to perceive this room as a "palladium of Russian greatness and glory." In the hall of Peter I is historical relic- the throne of Empress Anna Ioannovna, made by master N. Clausen in London in 1731. The wooden base of the throne is framed in massive gilded silver, on the back is embroidered with silver National emblem Russia.

Petrovsky Hall. The Petrovsky (Small Throne) Hall commemorates the founder of the Russian Empire, Peter I. The hall was created in 1833 according to the project of O.-R. Montferrand (1786-1858) and restored after a fire by V.P. Stasov almost unchanged. The decoration of the hall was the composition with the allegorical painting "Peter I with Minerva" by G. Amikoni. Elements of imperial paraphernalia - the monograms of Peter the Great, crowns, double-headed eagles - occupy a special place in the decoration of the hall. Picturesque images of the famous battles of the Northern War - the Poltava battle and the Battle of Lesnaya - allowed contemporaries to perceive this room as a "palladium of Russian greatness and glory." In the hall of Peter I is historical relic- the throne of Empress Anna Ioannovna, made by master N. Clausen in London in 1731. The wooden base of the throne is framed in massive gilded silver, on the back is embroidered with silver National emblem Russia.

slide 19

Winter Palace. 1853. An unprecedented fire completely destroyed the magnificent decoration of the royal residence, erasing an entire era in the history of the palace. It seemed that it would not be possible to revive the palace. However, the consequences of the fire were eliminated in an unprecedentedly short time: during 1838-1839. And in the spring of 1839, a large solemn reception dedicated to the resumption of the Winter Palace was held in the newly decorated state rooms. It can be argued that in terms of scale and complexity, this was an unprecedented restoration for its time, which the practice of world architecture did not know.

Winter Palace. 1853. An unprecedented fire completely destroyed the magnificent decoration of the royal residence, erasing an entire era in the history of the palace. It seemed that it would not be possible to revive the palace. However, the consequences of the fire were eliminated in an unprecedentedly short time: during 1838-1839. And in the spring of 1839, a large solemn reception dedicated to the resumption of the Winter Palace was held in the newly decorated state rooms. It can be argued that in terms of scale and complexity, this was an unprecedented restoration for its time, which the practice of world architecture did not know.

slide 20

Revival of the Winter Palace. The revival of the Winter Palace after the fire of 1837 is, first of all, the merit of two outstanding Russian architects of the 19th century - V.P. Stasov (1769-1848) and A.P. Bryullov (1798-1877). V.P. Stasov restored the front part of the palace and supervised the general construction work. The task before him was very difficult. In a short time, the architect had to not only restore the palace to its former splendor, but also give all the front halls a look that met the artistic tastes and views of the Nikolaev era - the time of the highest power of the Russian Empire, which became a great European power after the victory over Napoleon. This ideological side was especially insisted on by Tsar Nicholas I, who personally drew up a thematic program for the decoration of the restored halls. Finally, it was necessary to provide for all measures to forever exclude the possibility of a new fire. Stasov brilliantly solved this problem by creating a monumental complex of ceremonial halls, united by the nobility of the classical style and the idea of the greatness of the Russian Empire.

Revival of the Winter Palace. The revival of the Winter Palace after the fire of 1837 is, first of all, the merit of two outstanding Russian architects of the 19th century - V.P. Stasov (1769-1848) and A.P. Bryullov (1798-1877). V.P. Stasov restored the front part of the palace and supervised the general construction work. The task before him was very difficult. In a short time, the architect had to not only restore the palace to its former splendor, but also give all the front halls a look that met the artistic tastes and views of the Nikolaev era - the time of the highest power of the Russian Empire, which became a great European power after the victory over Napoleon. This ideological side was especially insisted on by Tsar Nicholas I, who personally drew up a thematic program for the decoration of the restored halls. Finally, it was necessary to provide for all measures to forever exclude the possibility of a new fire. Stasov brilliantly solved this problem by creating a monumental complex of ceremonial halls, united by the nobility of the classical style and the idea of the greatness of the Russian Empire.

slide 21

Revival of the Winter Palace. This idea found its expression in the grandeur of the halls, in the splendor and at the same time strict thoughtfulness and rationality of the decorations, in the richness of the materials used, in the motifs and plots of the wall paintings, stucco, paintings, sculptures, decorative objects, and finally, in the solemn rhythm in which the halls, following one after another, they line up in magnificent enfilades. All the main official palace ceremonies were held here: solemn receptions, high-society balls, the highest exits. The halls along the Neva and the Grand ceremonial suite, going deep into the Winter Palace to the Great Throne Hall, are connected by the Main Staircase. Immediately behind the Main Staircase was the first hall of the Grand Enfilade - the Field Marshal's. Here, officers of the palace guards were usually located and the palace guards were divorced. Decorated with portraits of Russian field marshals, the hall was supposed to remind of the military glory and power of the Russian Empire. Stasov recreated the Field Marshal's Hall the way Montferrand built it. In addition, in accordance with the plan of his predecessor, he restored the adjacent Petrovsky (Small Throne) Hall.

Revival of the Winter Palace. This idea found its expression in the grandeur of the halls, in the splendor and at the same time strict thoughtfulness and rationality of the decorations, in the richness of the materials used, in the motifs and plots of the wall paintings, stucco, paintings, sculptures, decorative objects, and finally, in the solemn rhythm in which the halls, following one after another, they line up in magnificent enfilades. All the main official palace ceremonies were held here: solemn receptions, high-society balls, the highest exits. The halls along the Neva and the Grand ceremonial suite, going deep into the Winter Palace to the Great Throne Hall, are connected by the Main Staircase. Immediately behind the Main Staircase was the first hall of the Grand Enfilade - the Field Marshal's. Here, officers of the palace guards were usually located and the palace guards were divorced. Decorated with portraits of Russian field marshals, the hall was supposed to remind of the military glory and power of the Russian Empire. Stasov recreated the Field Marshal's Hall the way Montferrand built it. In addition, in accordance with the plan of his predecessor, he restored the adjacent Petrovsky (Small Throne) Hall.

slide 22

Revival of the Winter Palace. The Armorial Hall next to Petrovsky was designed by the architect Stasov according to his own design. He significantly increased the length of the hall, and the area of the Armorial Hall (the second largest in the Winter Palace) now amounted to 1000 sq.m. Using the composition of the columned hall, characteristic of Russian classicism, the architect achieved the solemn imposingness of the heavy, entirely gilded columns of the luxurious Corinthian order, the upper galleries lying on them and the porticos framing the entrances. On both sides of the entrances there were sculptural groups - Russian knights with spears, on which shields with the coats of arms of the Russian provinces were fixed. (Now they are fortified along the edges of the gilded bronze chandeliers decorating the hall.) The coats of arms gave the name to the hall, which personified the unity of the empire and the emperor: the sovereign's receptions were held here for representatives of cities, provincial nobility, and estates. Today, the Armorial Hall, like many other halls of the Winter Palace, is an exhibition space. The Armorial Hall exhibits the richest collection of Western European silver of the 17th-18th centuries.

Revival of the Winter Palace. The Armorial Hall next to Petrovsky was designed by the architect Stasov according to his own design. He significantly increased the length of the hall, and the area of the Armorial Hall (the second largest in the Winter Palace) now amounted to 1000 sq.m. Using the composition of the columned hall, characteristic of Russian classicism, the architect achieved the solemn imposingness of the heavy, entirely gilded columns of the luxurious Corinthian order, the upper galleries lying on them and the porticos framing the entrances. On both sides of the entrances there were sculptural groups - Russian knights with spears, on which shields with the coats of arms of the Russian provinces were fixed. (Now they are fortified along the edges of the gilded bronze chandeliers decorating the hall.) The coats of arms gave the name to the hall, which personified the unity of the empire and the emperor: the sovereign's receptions were held here for representatives of cities, provincial nobility, and estates. Today, the Armorial Hall, like many other halls of the Winter Palace, is an exhibition space. The Armorial Hall exhibits the richest collection of Western European silver of the 17th-18th centuries.

slide 23

Armorial hall. Each subsequent hall of the Enfilade became another link in the complex picture of symbols glorifying the Fatherland. The Armorial Hall of the Winter Palace, intended for solemn ceremonies, was created by V.P. Stasov in the late 1830s. in the style of late Russian classicism. Images of coats of arms of Russian provinces are placed on gilded bronze chandeliers. The entrances to the hall are flanked by sculptural groups of ancient Russian warriors. A slender colonnade carrying a balcony with a balustrade, a frieze with an ornament of acanthus leaves, and a combination of gold and white create an impression of grandeur and solemnity.

Armorial hall. Each subsequent hall of the Enfilade became another link in the complex picture of symbols glorifying the Fatherland. The Armorial Hall of the Winter Palace, intended for solemn ceremonies, was created by V.P. Stasov in the late 1830s. in the style of late Russian classicism. Images of coats of arms of Russian provinces are placed on gilded bronze chandeliers. The entrances to the hall are flanked by sculptural groups of ancient Russian warriors. A slender colonnade carrying a balcony with a balustrade, a frieze with an ornament of acanthus leaves, and a combination of gold and white create an impression of grandeur and solemnity.

slide 24

Gallery of the Patriotic War of 1812. The Gallery of the Patriotic War of 1812 adjoins the Armorial Hall. All the portraits of the gallery during the fire were taken out of the fire and saved by the soldiers of the Guards regiments. Stasov was given the opportunity to restore the gallery to its original form. However, the architect made some changes to Rossi's plan, which gave the gallery a complete, solemnly austere and impressive appearance: the length of the first gallery was increased by almost 6 m, the choirs were placed above the cornice - a bypass gallery connected with the same galleries of neighboring halls. This was done not only to enhance the decorative effect, but also for firefighting purposes. Through the glazed covers built into the vaults, daylight now passed into the gallery, the wooden rafters of the ceilings were replaced with iron ones.

Gallery of the Patriotic War of 1812. The Gallery of the Patriotic War of 1812 adjoins the Armorial Hall. All the portraits of the gallery during the fire were taken out of the fire and saved by the soldiers of the Guards regiments. Stasov was given the opportunity to restore the gallery to its original form. However, the architect made some changes to Rossi's plan, which gave the gallery a complete, solemnly austere and impressive appearance: the length of the first gallery was increased by almost 6 m, the choirs were placed above the cornice - a bypass gallery connected with the same galleries of neighboring halls. This was done not only to enhance the decorative effect, but also for firefighting purposes. Through the glazed covers built into the vaults, daylight now passed into the gallery, the wooden rafters of the ceilings were replaced with iron ones.

slide 25

The widespread use of metal in the restoration of the palace was an innovation in the building practice of that time. Many metal structures, complex elements of the new heating system that replaced the stove, water pipes, metal parts of architectural decorations were made for the palace at the St. Petersburg Alexander Plant. The talented engineer M.E. Clark, who headed it, using the latest achievements of modern technical thought, brilliantly solved a number of complex technical problems that arose in the course of the work. He developed and for the first time used in the Winter Palace a system of unsupported ceilings using metal trusses and beams, to which ceilings made of copper sheets were hung. This system made it possible to create ceilings in such large halls as the Armorial and Great Throne Rooms.

The widespread use of metal in the restoration of the palace was an innovation in the building practice of that time. Many metal structures, complex elements of the new heating system that replaced the stove, water pipes, metal parts of architectural decorations were made for the palace at the St. Petersburg Alexander Plant. The talented engineer M.E. Clark, who headed it, using the latest achievements of modern technical thought, brilliantly solved a number of complex technical problems that arose in the course of the work. He developed and for the first time used in the Winter Palace a system of unsupported ceilings using metal trusses and beams, to which ceilings made of copper sheets were hung. This system made it possible to create ceilings in such large halls as the Armorial and Great Throne Rooms.

slide 26

The Great Throne Hall (Georgievsky) The Great Throne Hall, the main hall of the Winter Palace, completes the Grand Front Enfilade. The Throne Hall that existed here before the fire was created by the architect Quarenghi during the reign of Catherine II and consecrated on November 26, 1795 on the day of St. George the Victorious - the patron saint of the Russian state and army. Hence the second name of the hall - Georgievsky. His decoration was completely destroyed in the fire. Stasov redesigned the hall in a strict and majestic classical style: the grandiose space (the area of the hall is 800 square meters), rows of snow-white columns, the brilliance and heaviness of gilded bronze create a feeling of solemnity and splendor. Here, in the presence of the sovereign and the highest dignitaries of the Court, the most important state acts were performed, the main official ceremonies took place. The main theme of the design of the grand residence of the Russian emperors - the greatness and power of the empire, the Russian state - found its highest expression in the artistic design of the Great Throne Hall.

The Great Throne Hall (Georgievsky) The Great Throne Hall, the main hall of the Winter Palace, completes the Grand Front Enfilade. The Throne Hall that existed here before the fire was created by the architect Quarenghi during the reign of Catherine II and consecrated on November 26, 1795 on the day of St. George the Victorious - the patron saint of the Russian state and army. Hence the second name of the hall - Georgievsky. His decoration was completely destroyed in the fire. Stasov redesigned the hall in a strict and majestic classical style: the grandiose space (the area of the hall is 800 square meters), rows of snow-white columns, the brilliance and heaviness of gilded bronze create a feeling of solemnity and splendor. Here, in the presence of the sovereign and the highest dignitaries of the Court, the most important state acts were performed, the main official ceremonies took place. The main theme of the design of the grand residence of the Russian emperors - the greatness and power of the empire, the Russian state - found its highest expression in the artistic design of the Great Throne Hall.

slide 27

Malachite living room. Finishing and artistic decoration of the residential half of the palace after the fire of 1837 were entrusted to A.P. Bryullov, who created a complex of residential halves located on all three floors of the western part of the Winter Palace. With special luxury and sophistication, he decorated the rooms of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna - an enfilade with windows overlooking the Neva and the Admiralty. An outstanding talented architect, erudite, connoisseur of historical styles, in his projects he skillfully, with taste and tact used the techniques and traditions of the architecture of ancient classics, the European Middle Ages, the East. The decoration of the interiors in the half of Alexandra Fedorovna has not been preserved, but their appearance was brought to us by watercolors. Such was the order made by Nicholas I: he ordered the interiors of the Winter Palace and the Hermitage to be recorded in watercolors. Executed in the 1850s-1860s by the artists K.A. Ukhtomsky, E.P. Gaui L. Premazzi, watercolors are now invaluable documents that give an accurate and at the same time artistic representation of the imperial residence of the 19th century. The only hall, the decoration of which has been completely preserved to this day, is the Malachite Drawing Room. The hall owes its truly fabulous luxury to the famous Ural malachite, a rare and extremely valuable green stone. In 1835, a large deposit of malachite was found in the Ural mines in the possession of the Demidovs. More than two tons of malachite was donated by Demidov to the Tsar to decorate the living room in the palace. The malachite living room served as a link between the front halls of the palace and the rooms of the empress. Behind the Malachite Living Room, a number of personal chambers of Alexandra Feodorovna opened up: the Dining Room, painted based on the frescoes excavated in Pompeii, Italy, the elegant Living Rooms, the Bedroom, the cozy Boudoir, the romantic Winter Garden with a babbling fountain and exotic plants, the exquisite and luxurious Bathroom, decorated in Moorish style, as if filled with spicy aromas of the East.

Malachite living room. Finishing and artistic decoration of the residential half of the palace after the fire of 1837 were entrusted to A.P. Bryullov, who created a complex of residential halves located on all three floors of the western part of the Winter Palace. With special luxury and sophistication, he decorated the rooms of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna - an enfilade with windows overlooking the Neva and the Admiralty. An outstanding talented architect, erudite, connoisseur of historical styles, in his projects he skillfully, with taste and tact used the techniques and traditions of the architecture of ancient classics, the European Middle Ages, the East. The decoration of the interiors in the half of Alexandra Fedorovna has not been preserved, but their appearance was brought to us by watercolors. Such was the order made by Nicholas I: he ordered the interiors of the Winter Palace and the Hermitage to be recorded in watercolors. Executed in the 1850s-1860s by the artists K.A. Ukhtomsky, E.P. Gaui L. Premazzi, watercolors are now invaluable documents that give an accurate and at the same time artistic representation of the imperial residence of the 19th century. The only hall, the decoration of which has been completely preserved to this day, is the Malachite Drawing Room. The hall owes its truly fabulous luxury to the famous Ural malachite, a rare and extremely valuable green stone. In 1835, a large deposit of malachite was found in the Ural mines in the possession of the Demidovs. More than two tons of malachite was donated by Demidov to the Tsar to decorate the living room in the palace. The malachite living room served as a link between the front halls of the palace and the rooms of the empress. Behind the Malachite Living Room, a number of personal chambers of Alexandra Feodorovna opened up: the Dining Room, painted based on the frescoes excavated in Pompeii, Italy, the elegant Living Rooms, the Bedroom, the cozy Boudoir, the romantic Winter Garden with a babbling fountain and exotic plants, the exquisite and luxurious Bathroom, decorated in Moorish style, as if filled with spicy aromas of the East.

slide 28

Bedroom. The emperor's rooms were located on the third floor. And only the office of Nicholas I was downstairs, on the first floor. Every evening, the inhabitants of the capital could see the light in the window of the emperor's office and his figure leaning over the table. Here was his camp folding bed, on which he was destined to die in 1855. Behind the wall of the office were the rooms of the daughters of Nicholas I - Olga and Alexandra. This small enfilade of simply but elegantly decorated premises continued to be the prince's "children's half" even after the marriage of the grand duchesses.

Bedroom. The emperor's rooms were located on the third floor. And only the office of Nicholas I was downstairs, on the first floor. Every evening, the inhabitants of the capital could see the light in the window of the emperor's office and his figure leaning over the table. Here was his camp folding bed, on which he was destined to die in 1855. Behind the wall of the office were the rooms of the daughters of Nicholas I - Olga and Alexandra. This small enfilade of simply but elegantly decorated premises continued to be the prince's "children's half" even after the marriage of the grand duchesses.

slide 29

Library of Nicholas II Special apartments of the palace were intended for the heir - the Tsarevich, the future Emperor Alexander II. This Enfilade of chambers with windows overlooking the Admiralty was created by the architect Quarenghi during the time of Catherine the Great especially for Alexander I, then the Grand Duke. Following the instructions of Nicholas I, Bryullov did everything to recreate the decoration of Quarenghi in the Grand Duke's half. And in 1839, in connection with the upcoming marriage of the heir to the princess of Hesse-Darmstadt (future Empress Maria Alexandrovna), A.P. Bryullov was entrusted with the registration of a new half of the heir. This Enfilade began from the Stairs of Her Imperial Majesty, the current October Staircase, going from the Oktyabrsky entrance from the side of Palace Square. Bryullov retained the classically restrained and elegant decoration of the staircase, created by Montferrand before the fire. A series of luxuriously decorated halls followed from the stairs: the front White Hall (one of the best works of Bryullov in the Winter Palace), Living Rooms, Bedroom, Boudoir. These were the private quarters of the heir's wife, adjoining his own rooms. In the mid-1850s, a number of Maria Alexandrovna's rooms were re-decorated by well-known architects of that time: A.I. Shtakenshneider (1802-1865), who worked a lot in those years in the imperial residence, and Yu.A. Bosse. An outstanding master of historicist architecture, a subtle stylist, Stackenschneider created the most elegant rooms for Maria Alexandrovna - the Green Dining Room and the Raspberry Study. The whole life of Empress Maria Alexandrovna was spent in these apartments. She loved music and painting. Raspberry office, on the damask of which it was no coincidence that images of various musical instruments served as a venue for home concerts. Paintings hung on the walls of the study, which were often purchased especially for the Empress, and later became a valuable asset of the Hermitage.

Library of Nicholas II Special apartments of the palace were intended for the heir - the Tsarevich, the future Emperor Alexander II. This Enfilade of chambers with windows overlooking the Admiralty was created by the architect Quarenghi during the time of Catherine the Great especially for Alexander I, then the Grand Duke. Following the instructions of Nicholas I, Bryullov did everything to recreate the decoration of Quarenghi in the Grand Duke's half. And in 1839, in connection with the upcoming marriage of the heir to the princess of Hesse-Darmstadt (future Empress Maria Alexandrovna), A.P. Bryullov was entrusted with the registration of a new half of the heir. This Enfilade began from the Stairs of Her Imperial Majesty, the current October Staircase, going from the Oktyabrsky entrance from the side of Palace Square. Bryullov retained the classically restrained and elegant decoration of the staircase, created by Montferrand before the fire. A series of luxuriously decorated halls followed from the stairs: the front White Hall (one of the best works of Bryullov in the Winter Palace), Living Rooms, Bedroom, Boudoir. These were the private quarters of the heir's wife, adjoining his own rooms. In the mid-1850s, a number of Maria Alexandrovna's rooms were re-decorated by well-known architects of that time: A.I. Shtakenshneider (1802-1865), who worked a lot in those years in the imperial residence, and Yu.A. Bosse. An outstanding master of historicist architecture, a subtle stylist, Stackenschneider created the most elegant rooms for Maria Alexandrovna - the Green Dining Room and the Raspberry Study. The whole life of Empress Maria Alexandrovna was spent in these apartments. She loved music and painting. Raspberry office, on the damask of which it was no coincidence that images of various musical instruments served as a venue for home concerts. Paintings hung on the walls of the study, which were often purchased especially for the Empress, and later became a valuable asset of the Hermitage.

slide 30

Following the instructions of Nicholas I, Bryullov did everything to recreate the decoration of Quarenghi in the Grand Duke's quarter after a fire in 1837. In connection with the upcoming marriage of the heir in 1839 with the princess of Hesse-Darmstadt (future Empress Maria Alexandrovna), A.P. Bryullov was entrusted with the design of some of the halls of the heir. The enfilade, which began from the Stairs of Her Imperial Majesty, the current October, included the Crimson Cabinet. This hall was decorated by A.P. Bryullov in 1841 and was used as an office and dining room for Maria Alexandrovna. In the mid-1850s, a number of rooms of the wife of the future Emperor Alexander II were re-decorated by the famous architect of that time - A.I. Shtakenshneider, who worked a lot in those years in the imperial residence. An outstanding master of historicist architecture, a subtle stylist, Stackenschneider created the most elegant rooms for Maria Alexandrovna. In 1858 Stackenschneider changed the design of the Crimson Room. The vaults were removed and the ceiling redone; the upholstery was replaced, but its color remained the same - dark red. A considerable part of Maria Alexandrovna's life was spent in these apartments. She loved music and painting. The raspberry cabinet, on the damask of which it was no coincidence that images of various musical instruments were woven, served as a place for home concerts. Paintings hung on the walls of the study, which were often purchased especially for the Empress.

Following the instructions of Nicholas I, Bryullov did everything to recreate the decoration of Quarenghi in the Grand Duke's quarter after a fire in 1837. In connection with the upcoming marriage of the heir in 1839 with the princess of Hesse-Darmstadt (future Empress Maria Alexandrovna), A.P. Bryullov was entrusted with the design of some of the halls of the heir. The enfilade, which began from the Stairs of Her Imperial Majesty, the current October, included the Crimson Cabinet. This hall was decorated by A.P. Bryullov in 1841 and was used as an office and dining room for Maria Alexandrovna. In the mid-1850s, a number of rooms of the wife of the future Emperor Alexander II were re-decorated by the famous architect of that time - A.I. Shtakenshneider, who worked a lot in those years in the imperial residence. An outstanding master of historicist architecture, a subtle stylist, Stackenschneider created the most elegant rooms for Maria Alexandrovna. In 1858 Stackenschneider changed the design of the Crimson Room. The vaults were removed and the ceiling redone; the upholstery was replaced, but its color remained the same - dark red. A considerable part of Maria Alexandrovna's life was spent in these apartments. She loved music and painting. The raspberry cabinet, on the damask of which it was no coincidence that images of various musical instruments were woven, served as a place for home concerts. Paintings hung on the walls of the study, which were often purchased especially for the Empress.

slide 31

slide 32

White Hall. The White Hall was created by A.P. Bryullov for the wedding of the future Emperor Alexander II in 1841. This interior, kept in white tones, is distinguished by a rich plastic decor: stucco ornaments cover the vault and pilasters, the frieze ribbon is decorated with putti figurines indulging in games. In the central part of the hall, above the images of armor, there are bas-relief figures of ancient Roman gods; columns with magnificent Corinthian capitals are crowned with figures personifying the arts. The interior harmoniously looks picturesque panels of the French landscape painter of the 18th century. G. Robert. In the hall there is an exposition of furniture by D. Roentgen, the famous master of the era of classicism. During the reign of Emperor Alexander II, the hall had its own purpose: the festive receptions that took place then were held not in the northern part of the palace, as under Nicholas I, but in its southern section, where the personal rooms of the emperor and empress were located.

White Hall. The White Hall was created by A.P. Bryullov for the wedding of the future Emperor Alexander II in 1841. This interior, kept in white tones, is distinguished by a rich plastic decor: stucco ornaments cover the vault and pilasters, the frieze ribbon is decorated with putti figurines indulging in games. In the central part of the hall, above the images of armor, there are bas-relief figures of ancient Roman gods; columns with magnificent Corinthian capitals are crowned with figures personifying the arts. The interior harmoniously looks picturesque panels of the French landscape painter of the 18th century. G. Robert. In the hall there is an exposition of furniture by D. Roentgen, the famous master of the era of classicism. During the reign of Emperor Alexander II, the hall had its own purpose: the festive receptions that took place then were held not in the northern part of the palace, as under Nicholas I, but in its southern section, where the personal rooms of the emperor and empress were located.

slide 33

October staircase. This main staircase was restored after a fire in 1837 by A.P. Bryullov, who kept the project of O. de Montferrand (early 1830s) almost unchanged. The architectural solution of the stairs adjoining the private apartments is distinguished by the rigor and clarity typical of the classicism style. The theme of glory clearly sounds in the decor: a bas-relief located above the windows depicts a triumphal procession; the lunettes feature allegorical compositions of female figures bowed before a double-headed eagle; the niches contain statues of ancient deities. The interior is richly decorated with grisly paintings. In the center of the vault painting there is a medallion depicting Apollo's chariot. The name "October" stairs was given in memory of the revolutionary events of October 1917, when the assault troops entered the Winter Palace along it. The captured ministers of the Provisional Government were led out along the October stairs at 3 o'clock on the night of October 25-26, 1917.

October staircase. This main staircase was restored after a fire in 1837 by A.P. Bryullov, who kept the project of O. de Montferrand (early 1830s) almost unchanged. The architectural solution of the stairs adjoining the private apartments is distinguished by the rigor and clarity typical of the classicism style. The theme of glory clearly sounds in the decor: a bas-relief located above the windows depicts a triumphal procession; the lunettes feature allegorical compositions of female figures bowed before a double-headed eagle; the niches contain statues of ancient deities. The interior is richly decorated with grisly paintings. In the center of the vault painting there is a medallion depicting Apollo's chariot. The name "October" stairs was given in memory of the revolutionary events of October 1917, when the assault troops entered the Winter Palace along it. The captured ministers of the Provisional Government were led out along the October stairs at 3 o'clock on the night of October 25-26, 1917.

slide 34

The Winter Palace from 1917 to 1925 The revolutionary upheavals of 1917 had a dramatic effect on the fate of the Winter Palace. In July, it was made its residence by the Provisional Government, which was located in the former chambers of Nicholas II. Anticipating the revolutionary events in the country, valuable palace property and Hermitage collections are sent to Moscow to be preserved in the Kremlin. After the capture of the Winter Palace by storm on the night of October 25-26, 1917, soldiers and sailors rioted in the royal apartments for three days, plundering the interior. Only a few days later, on October 30, 1917, the Winter Palace was declared the State Museum in the name of the Russian Soviet Republic by the new government. In 1925-1926, according to the design of the architect of the State Hermitage A.V. Sivkov, the reconstruction of numerous office premises began with the aim of using them for the expanding expositions of the Hermitage. The mezzanine floors that distorted the Rastrelli and other galleries, as well as corridors, a number of internal stairs, kitchens, service rooms, and later partitions were destroyed. A great achievement of the Winter Palace restorers was the reconstruction in 1938 of one of the few surviving Rastrelli interiors - the Rastrelli Gallery. On the third floor along the eastern facade of the palace, where sixty-four maid of honor rooms used to be, after the reconstruction of the original layout, seventeen bright halls were formed.

The Winter Palace from 1917 to 1925 The revolutionary upheavals of 1917 had a dramatic effect on the fate of the Winter Palace. In July, it was made its residence by the Provisional Government, which was located in the former chambers of Nicholas II. Anticipating the revolutionary events in the country, valuable palace property and Hermitage collections are sent to Moscow to be preserved in the Kremlin. After the capture of the Winter Palace by storm on the night of October 25-26, 1917, soldiers and sailors rioted in the royal apartments for three days, plundering the interior. Only a few days later, on October 30, 1917, the Winter Palace was declared the State Museum in the name of the Russian Soviet Republic by the new government. In 1925-1926, according to the design of the architect of the State Hermitage A.V. Sivkov, the reconstruction of numerous office premises began with the aim of using them for the expanding expositions of the Hermitage. The mezzanine floors that distorted the Rastrelli and other galleries, as well as corridors, a number of internal stairs, kitchens, service rooms, and later partitions were destroyed. A great achievement of the Winter Palace restorers was the reconstruction in 1938 of one of the few surviving Rastrelli interiors - the Rastrelli Gallery. On the third floor along the eastern facade of the palace, where sixty-four maid of honor rooms used to be, after the reconstruction of the original layout, seventeen bright halls were formed.

slide 35

Winter Palace in war time. Simultaneously with the reconstruction, the current restoration of the Armorial, Alexander and White Halls, the Great Church, the Gallery of 1812 was carried out. Unfortunately, during the alteration and adaptation of the former apartments of the royal family to accommodate art collections, fireplaces and stoves, which were of artistic value, were dismantled. In the 1930s, the Ammos heating system was liquidated, and the Winter Palace was connected to the city heating network. In 1939, a commission, which included representatives of the Department for the Protection of Monuments, the chief architect of the Hermitage, and other engineering and technical workers, drew up an act on the technical condition of the Winter Palace and determined a list of repair and restoration work. On May 10, 1941, the Leningrad City Executive Committee considered the issue of repairing and painting buildings overlooking Palace Square. But all the planned work was interrupted by the war ...

Winter Palace in war time. Simultaneously with the reconstruction, the current restoration of the Armorial, Alexander and White Halls, the Great Church, the Gallery of 1812 was carried out. Unfortunately, during the alteration and adaptation of the former apartments of the royal family to accommodate art collections, fireplaces and stoves, which were of artistic value, were dismantled. In the 1930s, the Ammos heating system was liquidated, and the Winter Palace was connected to the city heating network. In 1939, a commission, which included representatives of the Department for the Protection of Monuments, the chief architect of the Hermitage, and other engineering and technical workers, drew up an act on the technical condition of the Winter Palace and determined a list of repair and restoration work. On May 10, 1941, the Leningrad City Executive Committee considered the issue of repairing and painting buildings overlooking Palace Square. But all the planned work was interrupted by the war ...

slide 36

Alexander Hall. In 1834, A.P. Bryullov drafted a memorial hall in honor of Alexander I, which was completed only after the fire. The architect found a brilliant spatial solution for a huge double-height room. The original ceilings of the Alexander Hall - fan vaults bearing gently sloping domes - became its main architectural and artistic accent. The abundance of air, the grandiosity of the spaces under the dome allowed contemporaries to characterize the hall as made in the "Byzantine taste". The hall immortalized the memory of Alexander I: on the end wall was placed a portrait of the emperor by J. Doe, above it was a bas-relief with a profile image of Alexander “in the form of the Slavic deity Radomysl”, personifying wisdom and courage. The frieze was decorated with enlarged copies of the models of F.P. Tolstoy, telling about the events of the Patriotic War of 1812, and the symbolic figures of Slavs. The memorial character of the hall was emphasized by four huge battle paintings by G.P. Villevalde.

Alexander Hall. In 1834, A.P. Bryullov drafted a memorial hall in honor of Alexander I, which was completed only after the fire. The architect found a brilliant spatial solution for a huge double-height room. The original ceilings of the Alexander Hall - fan vaults bearing gently sloping domes - became its main architectural and artistic accent. The abundance of air, the grandiosity of the spaces under the dome allowed contemporaries to characterize the hall as made in the "Byzantine taste". The hall immortalized the memory of Alexander I: on the end wall was placed a portrait of the emperor by J. Doe, above it was a bas-relief with a profile image of Alexander “in the form of the Slavic deity Radomysl”, personifying wisdom and courage. The frieze was decorated with enlarged copies of the models of F.P. Tolstoy, telling about the events of the Patriotic War of 1812, and the symbolic figures of Slavs. The memorial character of the hall was emphasized by four huge battle paintings by G.P. Villevalde.

Slide 37

Big church. The interior of the Great Church, designed by F. B. Rastrelli, was one of the most magnificent in the Winter Palace. Restoring the church after the fire of 1837, V.P. Stasov sought to recreate its original appearance. The space is divided into three volumes, two of which - the one closest to the entrance and the altar part - are double-height. The central part is crowned with a dome and punctuated by pylons with double fluted columns of the Corinthian order. The walls are decorated with pilasters of the same order, which alternate with arched window openings that illuminate the church from two sides. A heavily profiled and unraveled cornice separates the first tier from the top row of windows. main role in the artistic decoration of the church play a gilded stucco ornament made of papier-mâché, and painting: the ceiling "Ascension of Christ" by P.V. Basin in the vestibule and images of the four evangelists on sails, created by F.A. Bruni. The interior decoration was complemented by crimson draperies and gilded lamps.

Big church. The interior of the Great Church, designed by F. B. Rastrelli, was one of the most magnificent in the Winter Palace. Restoring the church after the fire of 1837, V.P. Stasov sought to recreate its original appearance. The space is divided into three volumes, two of which - the one closest to the entrance and the altar part - are double-height. The central part is crowned with a dome and punctuated by pylons with double fluted columns of the Corinthian order. The walls are decorated with pilasters of the same order, which alternate with arched window openings that illuminate the church from two sides. A heavily profiled and unraveled cornice separates the first tier from the top row of windows. main role in the artistic decoration of the church play a gilded stucco ornament made of papier-mâché, and painting: the ceiling "Ascension of Christ" by P.V. Basin in the vestibule and images of the four evangelists on sails, created by F.A. Bruni. The interior decoration was complemented by crimson draperies and gilded lamps.

slide 38

The Winter Palace during the war years of 1941-1945 In the first days of the Great Patriotic War, many valuables of the Hermitage were urgently evacuated, some of them were hidden in the cellars. To prevent fires in the museum buildings, the windows were bricked up or closed with shutters. In some rooms, the parquets were covered with a layer of sand. The Winter Palace was a big target. A large number of bombs and shells exploded near him, and several hit the building itself. So, on December 29, 1941, a shell crashed into the southern wing of the Winter Palace overlooking the kitchen yard, damaging the iron rafters and the roof over an area of three hundred square meters, destroying the fire-fighting water supply installation located in the attic. The attic vaulted ceiling with an area of about six square meters was broken through. Another shell that hit the podium in front of the Winter Palace damaged the water main.

The Winter Palace during the war years of 1941-1945 In the first days of the Great Patriotic War, many valuables of the Hermitage were urgently evacuated, some of them were hidden in the cellars. To prevent fires in the museum buildings, the windows were bricked up or closed with shutters. In some rooms, the parquets were covered with a layer of sand. The Winter Palace was a big target. A large number of bombs and shells exploded near him, and several hit the building itself. So, on December 29, 1941, a shell crashed into the southern wing of the Winter Palace overlooking the kitchen yard, damaging the iron rafters and the roof over an area of three hundred square meters, destroying the fire-fighting water supply installation located in the attic. The attic vaulted ceiling with an area of about six square meters was broken through. Another shell that hit the podium in front of the Winter Palace damaged the water main.

Slide 39

Winter Palace during the war. Despite the difficult situation that existed in the besieged city, on May 4, 1942, the Leningrad City Executive Committee ordered construction trust No. 16 to carry out priority restoration work in the Hermitage, in which emergency repair workshops took part. In the summer of 1942, the roof was blocked in places where it was damaged by shells, the formwork was partially repaired, installed in broken skylights or iron sheets, the destroyed metal rafters were replaced with temporary wooden ones, and the plumbing system was repaired.

Winter Palace during the war. Despite the difficult situation that existed in the besieged city, on May 4, 1942, the Leningrad City Executive Committee ordered construction trust No. 16 to carry out priority restoration work in the Hermitage, in which emergency repair workshops took part. In the summer of 1942, the roof was blocked in places where it was damaged by shells, the formwork was partially repaired, installed in broken skylights or iron sheets, the destroyed metal rafters were replaced with temporary wooden ones, and the plumbing system was repaired.

slide 40

Winter Palace during the war. On May 12, 1943, an air bomb hit the building of the Winter Palace, partially destroying the roof over the St. George Hall and metal truss structures, and damaging the brickwork of the wall in the pantry of the Department of the History of Russian Culture. In the summer of 1943, despite the shelling, they continued to seal the roof and ceilings with tarred plywood, skylights. On January 2, 1944, another shell hit the Armorial Hall, severely damaging the finish and destroying two ceilings. The shell also pierced the ceiling of the Nicholas Hall. But already in August 1944, the Soviet government decided to restore all the buildings of the museum. Restoration work required huge efforts and stretched out for many years. But, despite all the losses, the Winter Palace remains an outstanding monument of baroque architecture.

Winter Palace during the war. On May 12, 1943, an air bomb hit the building of the Winter Palace, partially destroying the roof over the St. George Hall and metal truss structures, and damaging the brickwork of the wall in the pantry of the Department of the History of Russian Culture. In the summer of 1943, despite the shelling, they continued to seal the roof and ceilings with tarred plywood, skylights. On January 2, 1944, another shell hit the Armorial Hall, severely damaging the finish and destroying two ceilings. The shell also pierced the ceiling of the Nicholas Hall. But already in August 1944, the Soviet government decided to restore all the buildings of the museum. Restoration work required huge efforts and stretched out for many years. But, despite all the losses, the Winter Palace remains an outstanding monument of baroque architecture.

slide 41