Scotland has its own everything: crown, parliament, money*, language and even its own measures of length. The Scottish mile is longer than the English mile by as much as 200 meters and is just over 1800 meters. This is how long the road takes from Edinburgh Castle to Holyrood Palace. This is the Royal Mile. It consists of four streets flowing into each other:

- Castlehill is the shortest of the four and leads from the castle to the Hub. It houses the Camera Obscura and the Scotch Whiskey Museum.

- The Lawnmarket runs from the Hub to Bank Street. In the photo below we see it all.

- High Street is partially pedestrianized.

- Canongate is the most modest of the four.

N.B. If your English is okay, I recommend downloading it.

Photo above: View of the Hub from Bank Street. The yellow arrows of cranes near the castle are visible on the horizon. The Hub - the former St John's Church - is now home to the Edinburgh international festival.

Pictured above: a multi-storey building on Lonmarket.

From the main streets there are a bunch of offshoots that lead into courtyards and hidden squares, and sometimes into neighboring streets. Such alleys are called “close”. One of them is located in this house and leads to a very interesting courtyard.

Opposite is Gladstone's Land, a 17th-century tenement building.

In the photo above: the entrance to Gladstone's Land. Above the sign you can clearly see a gilded copper hawk with a rat in its talons. The knowledge houses a gift shop, a museum and an art gallery.

Pictured above: patio. There is a museum dedicated to three great Scottish writers whose names are known throughout the world: Walter Scott, Robert Stevenson and Robert Burns.

Emerging back into Lonmarket, look out for the black and white pub with a bandit on the sign.

Pictured above: a pub named after William Brodie, a respectable merchant and deacon (president) of the corporation, who looked like an honorable gentleman by day and was a bandit by night. His story formed the basis of Robert Stevenson's novel Strange story Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde."

In fact, the history of Edinburgh is full of dark characters and dubious deeds. They say Edinburgh is a haunted place. Perhaps Edinburghers are only luring tourists with these stories, or perhaps this is true. I personally have not met any ghosts. However, I didn’t go on excursions to dark places, and my independent visit to the Greyfriars Kirkyard cemetery was quite peaceful for me.

At this junction Lonmarket ends and the High Street begins, in my opinion the most beautiful part of the Royal Mile.

Pictured left: St Giles, pictured right: Tron Kirk.

Don't forget to look into the alleys. Of particular interest are Advocates Close and Anchor Close. The first offers a wonderful view of the Scott Monument, and the second is associated with the life of the poet Rothert Burns. If you're interested in Edinburgh's dark past, check out The Real Mary King's Close.

The Supreme Court building is located on the corner of High Street and Bank Street. There I found a bagpiper dressed in a kilt:

N.B. In a Scottish court, the accused can receive one of three verdicts: “guilty”, “not guilty” and “not proven”. According to the law, a verdict of “not proven” is acquittal, although it is given to someone whose guilt the court does not doubt, but cannot prove it. This is exactly the verdict that David Tennant’s character received in the mini-series “The Escape Artist.”

Photo above: St Giles, underground shot of the chandelier in the cathedral and the animal on the monument in front of the cathedral.

As you leave the cathedral, pay attention to the pavement.

Pictured above: The granite mosaic Heart of Midlothian marks the site of the former Old Tolbooth prison, demolished in 1817.

There is one strange tradition associated with the Heart of Midlothian: it is spit on. Visitors - in order to definitely return to Edindurg, locals - to find good luck. In reality, people spat on this place to express contempt for the prison.

In the photo above: Mercat Cross is a symbol of power, the official center of the city. At the top there is a sculpture of a royal unicorn.

The City Chambers arches are visible behind the Adam Smith monument. Unfortunately, I found this place during reconstruction, so there was nothing to admire. Judging by the photo on the right (by Chris Merrall), the building is quite interesting. We boldly head under the arches and find there the handprints of the Edinburgh Award winners:

Pictured above: J. K. Rowling's handprints in the upper right corner.

Pictured above: High Street.

This part of the street is pedestrian. There are many cafes and shops around, mostly, of course, aimed at tourists. I couldn’t resist and bought myself a ring with a thistle flower: Nemo Me Impune Lacessit!**

In the photo above: on the right with lattice windows is the house of John Knox, built in 1490.

The High Street pub ends (in fact begins, because house number one is located exactly opposite) with a pub with the telling name “The World's End” - “The End of the World”.

In the photo above: The World's End pub.

Somewhere between John Knox's house and The World's End, I came across a cartoon drawn on A3 sheet of paper and displayed in the window of a small shop. A colorful guy in a kilt was sitting on a chair nearby.

The contented, narrow Canongate leads us further to Holyrood Palace. It contains a couple of period schools, Canongate Church and the People's History Museum of Edinburgh, but is generally less attractive than the High Street or Lawnmarket.

Pictured above: a monument to the poet Robert Fergusson at Canongate Church.

Pretty soon you'll see on the right modern building The Scottish Parliament, which cost a pretty penny to build. From above it looks funny, but when you are close to it, there is no beauty at all. The panels that “decorate” the building cause a lot of controversy. Some see them as anvils, some as hair dryers, I looked at pistols. The architect's widow stated that these were curtains.

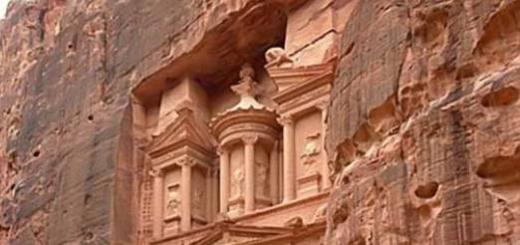

In general, it is better to ignore this miracle of complete architectural thought and head to the Queen’s current residence - Holyroodhouse Palace:

Pictured above: Palace of Holyroodhouse.

You can walk the Royal Mile in about 20 minutes at a brisk pace, but if you poke your curious nose into every interesting place, visit museum exhibitions and pamper yourself with gifts, then it may take half a day to examine it. If you set out to explore the pubs of Edinburgh, then... :)

In any case, happy hunting!

* Three Scottish banks have the right to issue their own banknotes. These are pounds sterling and can be used to pay anywhere in the UK, but they have their own design.

Pictured above: Edinburgh on the £10 note.

** No one will touch me with impunity (lat.) - Scottish royal motto.

The Royal Mile street is an area of Edinburgh between Edinburgh Castle and the royal residence of Holyrood House. It is often called a street, but in fact it is four parallel streets with many branches, alleys and dead ends. The length of the Royal Mile is approximately one Scottish mile, which is equal to 1800 meters - that is, 200 meters longer than the traditional English mile.

The Royal Mile is part of the Old City, which was built up in the Middle Ages. Medieval Edinburgh was an unattractive and dirty place, the streets of the Royal Mile were terribly unsanitary, there was no sewage system, livestock were bred in dead ends and alleys, and so many people were crammed into cramped wooden buildings that there was no free space left in the rooms. In 1644, Edinburgh was struck by a plague epidemic, forcing the authorities to take extreme measures: one of the quarters in this part of the city was completely blocked to prevent the disease from spreading. No one was able to get out; all the residents of the block died. They say that since then ghosts have been roaming the streets of the Royal Mile.

Beneath the modern pavements lie the same medieval streets. Late buildings, starting from the 18th century, were built directly on top of the old city. The Locked Quarter, later named after Mary King, the owner of most of the buildings, lies beneath the picturesque streets of Edinburgh city centre. Tourists are offered to go down to unusual excursion V ancient city plague, in which there is no light left. Dark tunnels are illuminated by dim bulbs, the wooden doors of old houses lead into cool, damp rooms where wine cellars, ovens, and cupboards have been preserved.

The modern Royal Mile is friendlier and livelier. It has four main streets - Castlehill, Lawnmarket, High Street and Canongate. The streets, according to medieval tradition, are quite winding, with narrow pavements; they often branch and intersect with other streets.

Castlehill Street is home to the Scottish Whiskey Heritage Centre, the headquarters of the Edinburgh International Festival called the Hub in a former cathedral building and the Museum of Illusions. Lonmarket is a street of souvenir shops and stores selling woolen items, tartan plaids, and kilts. Previously, there was a linen market here.

High Street is the center of the city's cultural and social life, where artists and street musicians gather, dressed in national kilts. On it are the buildings of the old Scottish Parliament and St. Giles' Cathedral, near which a heart is laid out on the pavement. It is called the “Heart of Midlothian”; according to tradition, tourists spit in it to return to Edinburgh. Few people remember the origin of this custom: there used to be a prison here, and when it was demolished, local residents they spat on this place as a sign of contempt for the authorities. The Edinburgh Folk History Museum and Canongate Church are located on Canongate Street.

This is just a sampling of all the attractions on the Royal Mile. Walking along its streets, you can see the monument to Adam Smith, the Cathedral of St. Egidio, the John Nash House Museum, the Museum of Childhood, and the handprints of Edinburgh Award winners (including the British writer JK Rowling).

The Royal Mile is beautiful in the evenings, illuminated by lanterns. Modern illumination does not disturb the medieval atmosphere of the Old Town. Night excursions through dark alleys, church cemeteries and courtyards of the Royal Mile are no less popular than daytime walks.

Royal Mile

Old city approaches the very foot of the castle walls. From the castle gates its main street begins, which runs along the ridge crest to royal palace Holyrood. In Scotland, the main streets are usually called "high streets". In Edinburgh, one of the sections of the road from the castle to Holyrood also bears this name, and the entire route was called the Royal Mile, which is still used today.

Originally, in the Middle Ages, the Royal Mile consisted of two parts. The top one gravitated towards the castle. Its center was St. Giles Church, the stone crown of which still forms an integral decoration of the Edinburgh skyline. This upper part of the Royal Mile belonged to Edinburgh proper. The lower part of the Royal Mile was called Canongate, that is, the street of canons-monks. Today it leads directly to the gates of Holyroodhouse Palace, and its name recalls the fact that the palace grew up in close proximity to the Augustinian abbey of the same name.

Everything in the Old Town is full of originality. And although today there are few houses here that were built more than three hundred years ago, the very principle of development has remained the same, and the city has retained its medieval topography. Moreover, carefully preserving the memory of their historical past, Edinburgh residents often mark with special blocks built into the pavement those places where buildings of historical significance that have not survived to this day once stood.

If you look at the early plans of Edinburgh, it will seem that the Old Town resembles the sprawled skeleton of some fantastic creature with an incredible number of ribs. Narrow lanes branch off from the main street, the Royal Mile, steeply descending from the slopes of the ridge. In Edinburgh they are called "closes" - dead ends. In the depths of each of them there were farmsteads. Later, these narrow dead ends became passages through “lands” - “lands”, that is, areas of land that were built up with houses. The names “closes” and “lands” have survived to this day. The latter designates not only a plot of land, but also a building standing on it. The system of such a city layout itself developed in the 14th century, during the time of Bruce. At that time, about two thousand people already lived in the city. Until this time, Edinburgh was simply a cluster of dwellings at the foot of the castle.

The old city had a very limited area for construction. He gravitated towards the castle, seeking its protection. More than once it was surrounded by wall belts that prevented its growth in breadth. And yet, in the 15th century, when Edinburgh became the capital, there were still gardens on the slopes of the ridge behind the houses. However, after the terrible defeat at Flodden in Northumbria in 1513, when both King James IV and “the entire flower of the Scottish nation” died in battle, the city was urgently surrounded by a wall, called Flodden, for which they were afraid to endure for the next two and a half centuries building. Meanwhile, the population grew. By the middle of the 18th century, Edinburgh already had about sixty thousand inhabitants. The city was built up very closely, and houses in dead ends and alleys grew higher and higher. Some of them reached a height of seven or eight floors. There were even ten-story buildings, and in some cases even taller ones. The rich lived in the lower floors, the poor lived in the upper floors. The old city on the ridge was not like English low-rise cities spread over a large area, but rather like continental cities. Much of it was reminiscent of old Paris. And not only the conditions of the growth of the city, limited by walls, but also the long-standing connections of the Scottish court with France, including contacts in the field of culture, were the sources of such similarities. It is known, for example, that the royal building workshops were oriented towards French tastes. In general, outside the circles associated with the court, the national architecture of Scotland was not affected by French influences, but in urban, especially Edinburgh architecture, they still appeared. Having a city house, in addition to a country residence, was considered mandatory for those seeking a career at court. The one who provided services to the court settled in such a way as to show his closeness to it, naturally, following the court tastes.

Among the various types of city houses, there were often traditional, continental buildings, with a narrow facade facing the street, with high roof ridges, with a large number of different buildings in the depths behind the facade.

In the 19th century, when the Edinburgh nobility for the most part moved to what had grown by that time New town, old Edinburgh began to decline. Multi-storey buildings, in which both the poor and the rich had previously lived, became a shelter only for the poor, and the city on the rock gradually acquired a slum character. In 1878, the first major clearing of the dark and dirty streets was undertaken. Many old houses were demolished, replacing them with new ones, but they did not particularly improve the situation in the city: the so-called Victorian era - the time of the long reign of Queen Victoria - was marked by the creation of extremely large quantity uncomfortable, gloomy and faceless residential buildings. The clearing left a lot of empty space, especially on Canongate Street. Unsanitary conditions continued to exist well into the 20th century. Only in the post-war years, according to the plan for the reconstruction and further development of Edinburgh, was serious attention paid to putting the Old Town in order.

To explore the Royal Mile, where there are many reminders of Edinburgh's historical past, it is better to walk from the castle down to Holyroodhouse Palace. The attractions of the Royal Mile are very different: these are small museums, historical buildings and memorial sites, or simply individual monuments reminiscent of some fact or event.

The esplanade in front of the castle forms the first section of the Royal Mile. The feeling of a person leaving the castle onto the esplanade can be compared to the feeling you experience when a subway car breaks out of an underground tunnel into the light and space of the surface line, only to dive back into the narrow mouth of the tunnel a minute later. You leave the castle by walking under the low passages of the gate towers along a narrow, rocky, dark road sandwiched between the walls. Step - and now the bright sun is blinding your eyes, and the fresh Edinburgh wind is ready to pick you up, carry you along the wide surface of the esplanade, press you against the barrier enclosing it, behind which a steep cliff begins. Far below lie the southern quarters of the Old City. The trellises of greenery reveal the Grassmarket - a former hay market and one of the memorable places in the Old Town, a witness to the executions of which there were so many in the life of medieval Edinburgh. A little further away, a large building with turrets is clearly visible. This is the so-called Heriot School, a building built for charitable purposes in the 20s of the 17th century by the court jeweler George Heriot, and at the same time one of the most interesting architectural monuments Edinburgh.

To the left of the esplanade you can see the New Town quarters with its beautiful Princes Street.

"Witch's" spring on the esplanade in front of Edinburgh Castle

Standing on the esplanade, not everyone, however, can guess that at this time he is on land that does not belong to Edinburgh. It turns out that back in the 17th century, King James I donated part of the territory near the esplanade to the barons of Nova Scotia (Canada). The decree was never canceled. Thus, oddly enough, according to the letter of the law, the part of the land located in the very center of the city does not belong to the city. A memorial plaque on the esplanade, near the place where the drawbridge used to be, reminds of this curious fact.

At the opposite edge of the esplanade there is the oldest city source of drinking water. Other springs, already clad in stone in ancient times, originate from it. They are located throughout the Royal Mile. Once upon a time, water carriers gathered there to carry water to homes. The spring near the esplanade was called “witch’s”. The stone slab mounted above it is a memory of the fact that three hundred years ago women accused of witchcraft were burned here. And this happened in a city where book printing had already existed since the 16th century, and the printing house itself was literally two steps away from the “witch’s” source!

Beyond the esplanade, the Royal Mile turns into a narrow and steep street called Castle Hill. The first building, standing on the left side of the street, is of significant interest. In Edinburgh it is known as the Observation Tower. Mounted on its roof, a pinhole camera casts images of houses and surroundings onto a white curved table in an upstairs room. The initiator and creator of the Observation Tower was Sir Patrick Geddes (1854-1932) - a bright and original figure in the history of Scottish culture of the late 19th - early 20th centuries. In the years of Scotland's final loss of its independence and the deep crisis of Scottish culture, Patrick Geddes, standing on a par with such major figures as the architect Mackintosh and the artist Mac Taggart, advocates for the renewal and independence of Scottish culture. Geddes' house on Castle Hill Street, built by him according to his own design, became a meeting place for Scottish artists and writers. Geddes himself published a review devoted to issues of Scottish culture and called “The Everlasting Wreath,” which emphasized the continuity of Scottish traditions: the same name was given to a collection of poems by the first major poet of Scotland in the 18th century, Alan Ramsay. Geddes's immediate profession was botany. However, he is known mainly as an educator. Fascinated by the history of city planning, Geddes collected a whole collection of paintings, maps and diagrams telling about Edinburgh, and considered it necessary to provide explanations for them for everyone who came to his “museum”. In order to instill in his compatriots an interest in studying their native land, Geddes also built the Ferris Tower.

Anyone traveling along the Royal Mile cannot fail to notice the huge building of the Church of St. John's, which formerly belonged to the former Edinburgh Town Hall. In old Edinburgh the town hall was called the Tolbooth, and this church is known in Edinburgh as the Tolbooth St John, in contrast to the other church of the same name at the end of Princes Street. The building, built in the 19th century in the spirit of Gothic architecture by Gillespie Graham, attracts attention with its seventy-meter spire. This is the most high point Edinburgh.

St Giles Church

The next section of the Royal Mile, called Lawnmarket, begins from the Tolbooth St. John Church.

Once upon a time, fabric merchants stood on this street with their stalls. And at the beginning of the 18th century it became a place where nobles, artists, and writers settled. Restoration work carried out in last years, allow you to see and appreciate some of the most remarkable buildings located here. Of particular interest architecturally is Gladstone Land, a multi-storey gloomy building typical of old Edinburgh with a narrow façade topped by a stepped pediment. Main entrance into the building - on the second floor, and an external staircase leads to it. The ground floor retains loggias very characteristic of old Edinburgh buildings; Due to such open galleries, the width of the narrow streets of the Old Town increased.

"Crown" of St Giles Church

In all of Edinburgh, this is the only example of an architectural design that was so characteristic of the Old Town in the past. A number of buildings have memorial significance. Thus, in the recently restored Ridle Close house, the famous Scottish historian and philosopher David Hume wrote his famous “History of England”. Robert Burns lived in Baxter's Close, adjacent to Gladstone Land, in 1786. Some houses on the Lawnmarket are associated with famous literary works. For example, a house called Brodie Land is associated with R. Stevenson's story "Dr. Jekyll and Mister Hyde." It is believed that Dean Brodie lived in this house in the 18th century, a respectable citizen by day and a robber by night, who served as the prototype for the main images of the mentioned work by Stevenson. Nearby is an ancient building (1622) named after its owner, Lady Stears. There has been an exhibition of materials on the history of Edinburgh here since 1907. The collection of exhibits associated with the name of Robert Burns is especially significant.

Not far from Lady Stears's house, the Royal Mile is crossed by the George IV Bridge, and a little further away - South Bridge. True, they don’t look like bridges – they’re just streets. The George IV Bridge is even considered one of the most advanced streets in Europe: it is equipped with special electrical equipment for melting ice in the winter. They are called bridges because they connect the mountain ranges on which Edinburgh lies. Immediately after the George IV Bridge, the most important part of the Royal Mile begins - the High Street. Here, between George IV Bridge and the South Bridge, is Parliament Square, which arose near one of the oldest buildings in Edinburgh, its main church, St. Giles, sometimes called the cathedral. Already from the esplanade, this black and gray church building, crowned with a mighty stone “crown,” is clearly visible. Since time immemorial, it was on this site that churches were built that bore the same name and were destroyed either by fires, or by military raids, or by later reconstructions. The current church mainly dates back to the 14th-15th centuries. It is known that there was a stone church of St. Giles already around 1120. Little remains of it - octagonal support pillars on which the tower rests, built at the end of the 15th - beginning of the 16th century and which has come down to us in its original form. The “crown” crowning the tower and formed by eight flying buttresses replaces the traditional spire of Gothic cathedrals, which is specific to the national forms of Scottish Gothic. It is the originality and beauty of its outlines that determine unique look the entire building. However, visible from many places in Edinburgh, this “crown” plays a significant role in the skyline of the city.

Three-aisled in plan, with two strongly projecting transepts, St Giles' Church is perceived as a mighty, monolithic mass. The tower under the crown, located in the center of the building, seems to bring all its parts together, especially since the towers flanking the western façade, characteristic of Gothic cathedrals, are absent here. Unfortunately, the church was badly damaged by 19th-century restorations. The surface of the walls has been reworked and finishing details have been replaced. Niches appeared on the facade, into which the sculpture was never placed. Fortunately, funds for “improving” the building were exhausted before restoration of the “crown” and tower began, thereby preserving the original medieval masonry. The interior of St. Giles's has also been largely preserved, with its mighty supporting pillars supporting complex stone ribbed vaults. Colored with colorful antique Scottish regimental banners, this interior is quite impressive.

"The Heart of Mid Lothian"

Initially, the church was designed for magnificent Catholic worship with solemn, according to the rite, processions. But after the Reformation, when such a large space only began to interfere with the reading of a sermon by a Protestant pastor, the naves were blocked off with blank walls into several compartments. In the second half of the 16th century, St Giles was home to two different churches. One of these was the Town Hall Church of old Edinburgh. It was from her pulpit that John Knox, the head of the Reformation in Scotland, delivered his fiery sermons. The huge building also had room for a school, a city government office, a courtroom, a prison, a gallows storeroom and a weaver's workshop. These institutions were later moved to other buildings, and two more churches took their place. Thus, four churches existed under the roof of St. Giles until 1832, by 1883 there were only three of them left, and then the building was freed from partitions and the interior was returned to an appearance close to the original.

Passage to Parliament Square

Memorial plaques, of which there are many on the walls and even on the floor in St. Giles, speak of the events that took place here. One of them is quite interesting. It recalls the enormous indignation that was caused in Protestant Scotland by the attempt of Charles I, with the help of Archbishop Laud, to instill a Catholic doctrine alien to the Scots. The reading at St. Giles in 1637 of the first sermon according to the new prayer book introduced by Laud, close to the Catholic one, caused a riot. Parishioner Janet Geddes threw the stool she was sitting on at the priest's head, setting an example for the rest of the parishioners. The mass was disrupted. The Bishop of Edinburgh fled in shame. The place from which the stool was thrown is marked with a memorial plaque. The priest was also awarded a separate plaque as the first and last person to perform divine services according to the new prayer book in this cathedral.

IN medieval city The cathedral has always been the center of public life. On British Isles As a rule, a cross was erected at the cathedral, at which royal decrees were read and trade deals were concluded. The townspeople gathered here to watch various spectacles, both festive, cheerful, and cruel, fear-inducing scenes of executions. On the carriageway of High Street, near the wall of St. Giles, the place where such a cross was located is marked. The old cross ceased to exist in 1759 and was replaced in the 19th century by a new one, which still stands nearby. And just as before, according to centuries-old tradition, it is from this place that important decrees are proclaimed to the townspeople.

Near St. Giles there was also the old Edinburgh prison, which went down in history under the name Old Tolbut. Walter Scott describes it in his novel The Heart of Middle Lothian. As already mentioned, the word "tolbooth" in Scotland refers to the town hall, and the Old Tolbooth originally also played this role. Sometimes, in the 17th century, the Scottish Parliament met there. But in the 18th century the building became purely a prison building, which is not so strange considering that the town hall usually had a prison. In 1817 the prison was demolished. But where she stood, near the entrance to St. Giles, on the pavement, a design in the shape of a heart was laid out with large paving stones. Gloomy memories of the Old Tolbooth, as a symbol of bondage and oppression, have survived to this day and have resulted in a peculiar tradition: when passing by the “Heart of Middle Lothian”, a superstitious Scot will never forget to spit on the place where the Old Tolboot once stood.

National Library of Scotland. Upper hall

In the 30s of the 17th century, the parliament building, Parliament House, was built next to St. Giles, and Parliament Square arose. It is very small: in a city surrounded by walls, a place for a building, not to mention a square, could only be carved out with great difficulty. To get to it from High Street, you need to cross a narrow passage between St Giles and the wall of the Houses of Parliament. In the middle of this space, facing Parliament Square, stands the equestrian monument of Charles II. Completed in 1685, it is Edinburgh's oldest sculptured monument. Until recently, one could see a stone set into the pavement nearby with the initials I. K. (lohannes Knox) and the date 1572. This was how the grave site of the leader of the Scottish Reformation, John Knox, was marked. Today, the memorial inscription has been moved to the outer wall of St. Giles Church, where John Knox repeatedly delivered his sermons. Such a strange location of the grave is explained only by the fact that in order to create Parliament Square, it was necessary to level the cemetery at St. Giles, where John Knox was buried.

The Houses of Parliament, begun in 1632 and completed by 1640, have not survived to this day. It was a structure with high turrets, like those that can now be seen in Heriot's School in Edinburgh. At the beginning of the 19th century, the architect Reed began its reconstruction, and in 1829 it received that majestic façade, decorated with Ionic columns, which still exists today. Only if you look closely, you can find several old turrets on the roof. Fortunately, the most architecturally significant part of the old building has been preserved - Parliament Hall, which was directly intended for parliamentary meetings. As befits such a public space in the British Isles, the hall is famous for its wooden ceilings, shaped like the hulk of a ship with its keel upside down. Parliament met there until 1707, that is, until Scotland joined England.

Church "at the steelyard"

During the reconstruction of the 1820s, Parliament Hall became part of a new building, no longer parliamentary in purpose, but the Palace of Justice. However, the name Parliament House still remains for the entire building. Thus, Parliament House, also known as the Palace of Justice, now houses the Supreme Court of Scotland, Parliament Hall, in which lawyers today talk with their clients, as well as a wonderful library. There is a separate entrance to it - from the side of the George IV Bridge. Originating at the end of the 17th century as a law library, it became National Library Scotland. Now it includes not only first-class legal literature. It stores over 2,000,000 books and over 10,000 volumes of manuscripts. Among them are the manuscripts of John Knox, Burns, Walter Scott, Stevenson, the last letter from Mary Stuart to Henry III of France, in which she writes that her execution is scheduled for the next day; a letter from Charles I, written by him as a child in a neat, careful hand: “Dear Father, I am learning to decline nouns and adjectives.”

The library building itself, in fact, is already connected with the history of Edinburgh's New Town and is an outstanding monument of Scottish classicism. The upper hall of the library, crowned with a low dome covered with paintings, is especially beautiful. Strict rows of Corinthian columns, between which sculptural busts are placed, add solemn majesty to the interior. The lower hall is especially interesting because a unique heating system was used here: hot air walked on the iron legs of library tables.

John Knox House

If you return to the Royal Mile, you should pay attention to the spectacular building standing almost opposite St. Giles. Built already in the 18th century, historically it is nevertheless connected with this part of the Old Town. For a long time, trade transactions were carried out at the cross that stands next to St. Giles. It is no coincidence that it was decided to build the exchange building here. John Adam was appointed architect. The main work was carried out from 1753 to 1758. The building occupies three sides of a courtyard open towards the Royal Mile. The main facade with a central pediment is decorated with pilasters. The lower floor is decorated with loggias. It was assumed that merchants would enter into trade deals here. However, the exchange was not used for these purposes, although it had services and shops. Merchants continued to make their transactions right on the street, and the exchange building was adapted for the needs of the city magistrate. Slightly modified, this building still stands out among the houses of the Royal Mile, and it is also interesting to look at it from the New Town, since the northern facade of the exchange rises above an almost thirty-meter cliff.

The trade that took place near St. Giles determined the name of the nearby church - the Church of Christ "at the steelyard" or Throne Church. Once upon a time, correct weight was monitored here. In case of deception, the fraudster was hooked by the ear with the same steelyard with which his goods were weighed. Until recently, the steelyard church was associated with the merry Edinburgh tradition. IN New Year's Eve From here it was customary to start traveling to familiar houses in order to wish happiness to friends. But a woman or a fair-haired man, it was believed, would not bring good luck, so a man, and a dark-haired one at that, was always placed at the head of a noisy company, who was the first to cross the threshold of a friendly house. Previously, New Year's round dances were held around this church. Nowadays these customs are already dying out. But the church "at the steelyard" is still particularly popular among Edinburgh residents. Begun in 1637, it has come to us in its mid-19th century appearance, rebuilt after a fire.

The high street continues behind the steelyard church, after crossing the Royal Mile with the South Bridge.

Huntly House

This part of old Edinburgh has undergone significant redevelopment. A little to the left of the Royal Mile, at the confluence of the South and North Bridges, a noisy shopping mall. There are very few old buildings left in this section. But it is here that one of the most interesting buildings of old Edinburgh has been preserved - the house of John Knox, dating back to the 16th century. It immediately attracts attention, standing out among neighboring buildings with the picturesque asymmetry of its individual parts. Indeed, it seems that it consists of independent volumes. Each part of the house has its own height, its own location of windows. Sami window– of unequal sizes and placed at different heights, which gives the building a specific appearance, characteristic of residential buildings of the late Middle Ages. The building is basically stone, but it still has covered wooden galleries, or rather bay windows, hanging one above the other and contributing greatly to the overall picturesque impression. Uneven-height mezzanines and a sharp roof ridge with an intricate chimney complete the entire structure. John Knox is believed to have lived here and died in 1572. Today, the house houses a museum dedicated to the life of this outstanding figure in Scotland.

There is another museum opposite Knox's house. Its sign is a funny doll. This is a very original Museum of Childhood: a museum about children, but not for children, but for adults. It allows you to trace the history of children's games, exhibits various toys and is generally dedicated to the development of children's consciousness.

Just behind Knox's house the High Street ends. A dead end with the expressive name End of the World runs down from the mountain here, and on the pavement copper bars mark the place of the city gates and the famous defensive Flodden Wall that previously stood here. This is where old Edinburgh ended. The next section of the Royal Mile, called Canongate - the path of the canons, no longer belonged to Edinburgh itself, but to the Abbey and Holyrood Palace. And if initially artisans settled here and the street was connected with the history of the abbey, then later, in the 15th century, with the emergence of a palace next to it, the nobility began to settle here, building their houses closer to the royal palace. In the 19th century, sharing the fate of the entire Old Town, Canongate found itself in an abandoned state. Little changed after the slum clearance at the end of the 19th century. Later, modern shops and residential buildings were built on the site of vacant lots. In the post-war years, some old buildings were very well restored. For example, near the house of John Knox, you can now see restored old residential buildings standing on land plots with very exotic names: Morocco-land - Moroccan land, Shoemaker's land - shoemaker's land, Bible-land - biblical land. These houses, with arcades and high ridges, reminiscent of Gladstone Land, have, however, all the modern conveniences.

Canongate Tolbooth - Canongate Town Hall building

Among the most notable architectural monuments of Canongate Street is Huntly House, a residential building built around 1570 that belonged to one of Edinburgh's wealthiest families. Somewhat awkward, just like Knox's house, it immediately attracts attention unusual appearance. A low ground floor, made of rough, variously sized pieces of stone, with small, unequal windows placed at different distances from each other. A strongly protruding cornice separates this floor from the second, higher one, built of stone slabs; here the windows are wider, but their location on the facade is completely inconsistent with the window openings of either the first or third floors. Each floor exists as if on its own. The third floor, plastered, overhangs the first two. The building ends with three sharp gables, all of the same height but different in shape. Perhaps it is precisely in this awkwardness, in the lack of unification, that lies the beauty of these ancient buildings, the facades of which seem to reflect the stages of their growth. There is still a lot of medievalism in Huntly House and its contemporary Scottish houses. The facade is only the end of the building. Behind it, going deeper into the block, are hidden, irregular in plan, the remaining parts of this house. Since 1932, the municipal history museum of the city has been opened in Huntly House. Among its exhibits are relics associated with Mary Stuart and Walter Scott, two of Edinburgh's most popular figures of past eras, and many paintings and watercolors of views of old Edinburgh. The main value of the museum is the original text of the Covenant, dated February 28, 1638.

The exhibitions of the city history museum are also located in the building of Canongate Town Hall, located almost opposite Huntly House. In Edinburgh it is known as the Canongate Tolbooth. This is an expressive structure, of rough stone masonry, with a chain of small pediments, as if uniting the different parts of the facade. Built in 1591, the town hall is easily recognizable by its tall bell tower under a round, pointed roof. In turn, to upper corners This square tower perched two small round turrets under the same roofs. Later, a clock placed on a bracket was strengthened between them. The presence of another town hall near the Old Tolbut was explained by the fact that Canongate was located outside the walls of the Old City and was an independent area.

There is a cemetery next to the town hall. It arose around Canongate Church, built in 1688 by order of King James II. Its author, obviously, was the architect J. Smith (d. 1731) - one of the two largest representatives of early classicism, a style that arose in Scotland in the 70s of the 17th century. It is curious that in this building by Smith, as well as in some other early classical buildings in Edinburgh, echoes of the Gothic still make themselves felt.

The cemetery is also worth visiting. Robert Fergusson, the greatest Scottish poet of the 18th century, predecessor of Robert Burns, is buried there. It was Burns who erected the monument on his grave. Mrs. Agnes MacLeose, immortalized by Burns under the name Clarinda, also rests here.

Not far from the town hall and Huntly House there are several other architecturally interesting buildings from the late 16th – early 17th centuries. Among them, the rich Moray House especially stands out, with well-preserved closed galleries hanging over the lower floors, with elegant pyramidal finials on the gates. This building is associated with the names of famous political figures in Scotland in the 17th century. When English troops occupied Edinburgh in 1650, the house was Cromwell's residence.

And already leaving Canongate, it is worth paying attention to another interesting building located on the left side of the street. High on its wall is a plaque that states that in 1681 the Duke of York, the future King James II, won a round of golf against two Englishmen and that his partner was the shoemaker John Paterson. With his winnings, Paterson built the said house, which is widely known in Edinburgh as Golfers Land, the Golfer's House. This house is located almost at the very gate leading to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which constitutes a separate important chapter in the past and present of the city.

From the book Helicopters. Volume I author Ruzhitsky Evgeniy IvanovichMi-1 MVZ im. MILE Light multi-purpose helicopter Light multi-purpose helicopter Mi-1 at the MAKS-95 aerospace exhibition Development of the helicopter began in 1947 under the leadership of M. JT. Mil, who proposed a project for a light multi-purpose helicopter for military and civilian

From the author's book From the author's bookMi-4 MVZ im. MILE Transport-landing and multi-purpose helicopter Transport-landing and multi-purpose helicopter Mi-4 The Mi-4 helicopter is the first military transport helicopter in the domestic armed forces. The creation of the helicopter was accelerated by the increased role

From the author's bookMi-38 MVZ im. MILE Multi-purpose helicopter Multi-purpose helicopter Mi-38 In the 1980s, the Moscow Helicopter Plant began researching a new multi-purpose helicopter to replace the Mi-8 helicopters, which had been mass-produced since 1962 and had proven themselves in operation. In 1987, sketch work began

The Royal Mile is a series of streets in the very center of Edinburgh. As the name suggests, these streets are approximately one Scottish mile (~1800 meters) long. The Royal Mile connects two major historical landmarks ancient capital– Edinburgh Castle, located on Castle Hill and the Palace of Holyroodhouse, the residence of Scottish and then British monarchs.

The Royal Mile begins on the Castle Esplanade, built in the 19th century for military parades near Edinburgh Castle. It is now the site of the annual Edinburgh Festival. There really was a cannonball stuck in the wall of the “Cannonball House” - they say it was an accidental shot from the castle cannon.

Leading down from the Castle Esplanade is Castlehill, a small street where the Camera Obscura and World of Illusions, the Edinburgh Festival headquarters and the Church of Scotland Meeting Hall are located. Next comes the Lawn Market, a street where tourists will find many souvenir shops.

From the Lawn Market we find ourselves on High Street - the center of the Edinburgh Festival, during which the street is crowded with street performers, onlookers and tourists. On the left is the Supreme Court building, on the right is Parliament Square, where St. Giles' Cathedral stands. Next to the eastern entrance to the cathedral, the “Heart of Midlothian” is laid out in stone on the paving stones, an image marking the site of the former city outpost - the administrative, tax and judicial center of the city. When the building was demolished, the townspeople developed the habit of spitting on the place where it stood. The city authorities decided to place an image of a heart in this place - but this only led to the fact that now the townspeople are trying to hit the center with their spit. Tourists are presented with an ennobled legend: they say they spit on luck, but in essence this tradition personifies only disrespect for the authorities.

The middle of the Royal Mile is an intersection with bridges. North Bridge leads left into New Town onto Princes Street. To the right is the South Bridge, in which it is very difficult to see the bridge - it looks like an ordinary street with rows of shops on both sides. The Edinburgh Cellars are hidden under the bridge and can be accessed on a guided tour.

Behind John Knox's house the old boundaries of the city end. The fortified city gate of Netherbow once stood here. Behind them began the property of Holyrood Abbey, which is reflected in the name of the next part of the Royal Mile, Canongate Street (“canon” in English - church, canonical). Scottish kings often preferred to live in Holyrood Abbey rather than in the gloomy Edinburgh Castle, and in the early 16th century King James IV built a palace adjacent to the abbey. The palace is now the official residence of Elizabeth II in Scotland.

The Royal Mile in Edinburgh is the heart of the city and its main and world-famous street. Not a single tourist who has visited will be able to pass by it, since no matter where he goes, sooner or later, he will still end up on the Royal Mile.

The Royal Mile in Edinburgh got its name for a reason. It's called Miley because she total length is 1.8 km or by Scottish standards exactly 1 mile. It connects the two main attractions of the city -, on the one hand, and the current royal residence - Holyrood Palace, on the other hand. This is where the word “royal” appeared in the name of the street.

Structure of the Royal Mile of Scotland

Royal Mile in Edinburgh is actually made up of four stretches, each with its own name Castlehill, High Street, Lawnmarket and Canongate. In addition, it unites all the branches, squares, courtyards and tunnels, so if we consider it schematically, the Royal Mile will resemble the skeleton of a fish. Most often, it is the various branches from the main street that are of the greatest interest to tourists, as they can find a lot of unexpected things there.

The Royal Mile is the center of city events

The central part of the street is the most crowded place in the city. Royal Mile is not exclusively pedestrian, so tourists have to jostle on both sides of the busy road, between layouts with souvenirs or pastries. It is here that all significant city events are held - carnivals, parades, festivals. Sometimes, even on an ordinary weekday, you can see living statues, magicians, jugglers and bagpipers here.

The entire length of the Royal Mile can be covered in just 20 - 25 minutes, so there is no need for transport to get from Holyroodhouse Palace or Edinburgh Castle to the city center. In addition, only by walking you can see unusual shop windows, medieval-style squares and original restaurants. For example, the End of the World pub or the Deacon Brodie tavern, named after the robber and murderer who became the prototype for Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hite in Robert Stevenson's book.

What Edinburgh attractions can be found on the Royal Mile?

It is a mistake to think that the Royal Mile is just a street where you can stroll, go shopping or see a bagpiper in a traditional Scottish kilt. There are quite a few places here that are worth visiting or at least paying attention to. Not far from Edinburgh Castle is the Scottish Whiskey Heritage Centre, where you can see 3.5 thousand types of whiskey and learn what and how it is made.

The former St. John's Church can be seen from afar, as it is an ancient building highest on the Royal Mile. Concerts are currently held here, theatrical performances, and it is from here that all the festivals held in this area are managed. If in winter period There are few of them, but in the summer they are held every week, so this section of the Royal Mile is not crowded with the influx of tourists.

The center of religious life in Edinburgh is St. Egidio's Cathedral. The temple is striking in its scale and the relics stored in it. Honorary citizens of Scotland are buried here, including famous writer Robert Stevenson.

On the Royal Mile you can visit the Museum of Childhood, the Museum of Illusions, the People's History of the City Museum and the house museum of the Scottish reformer John Knox, and those thirsting for more vivid impressions may be interested in a walk through the Edinburgh crypts and underground tunnels near the South Bridge.

Edinburgh is considered an ancient city, and even its central street in the evening looks more like a medieval one than a modern one. To experience this, many tourists come to the Royal Mile at night, when there are almost no people around, and the whole environment simply breathes history. Some guides offer thrill-seekers to walk through the most intriguing places with mysterious history and flying ghosts in the dark - cemeteries, dungeons and dark squares.

The Royal Mile in Edinburgh: where is it located?

City center. You can get there by bus number 35.